Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

A microscopic menace

April 21, 2023

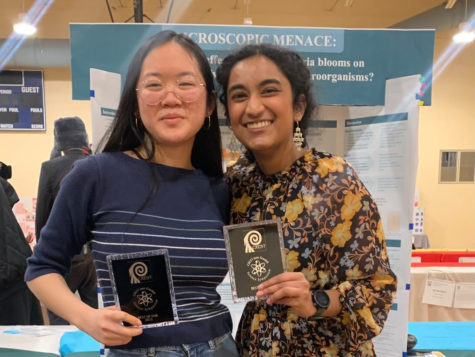

Some organisms can harm the environment without being recognized. Looking further into this issue, Uma Grover and Melinda Lin, seniors, have both had prior experience in ISEF with studying algae blooms. Last year, the duo made it to internationals with the same project, and decided to continue working on the experiment this year.

Grover and Lin studied algae blooms, which are created when toxic bacteria, known as cyanobacteria, bloom in large quantities. These blooms create toxic conditions and release harmful conditions for local ecosystems.

“We got in touch with some people at the United States Geological Survey and learned about the problem that algae blooms posed,” Grover said. “And upon hearing about that, we wanted to study that and figure out what we could do to help and contribute to the works of research already existing.”

The Willamette River’s Ross Island Lagoon is the origin of these algae blooms, which led to Grover and Lin choosing nearby sites to test and analyze the cyanobacteria. At the site, the water was stagnant and created a prime condition for cyanobacteria to grow. Grover and Lin chose sites above and below the lagoon to compare water samples.

Grover and Lin’s hypothesis was that the algae blooms would cause conditions of higher toxin levels in the water. They also hypothesized that the blooms were accompanied by conditions that were more eutrophic, or rich in nutrients, becoming more harmful for the organisms around them.

With their research over multiple months, beginning in April 2021 and still continuing with discoveries, Grover and Lin’s results supported their hypothesis. Originally, they believed that the amount of toxins in the water would directly correlate with the cyanobacteria in the water. However, they discovered that toxins were at their highest level when cyanobacteria levels were at their lowest. This led them to discover that when cyanobacteria die, the cells explode, and then the toxins get released. They also found that temperature was a way the toxins were being released, which is a new and emerging idea that was introduced in this field.

“The main thing about our results is they offer a potential alternative to predicting and quantifying cyanobacteria and their toxicity levels,” Lin said. “This is especially important because kits for measuring toxins are really expensive.”

Communities may not have access to expensive kits to measure the toxins in nearby bodies of water. Similar to the results found by this project, using temperatures to indicate the release of cyanotoxins, or melosira content, a diatom that can be associated with large algae blooms, can be sufficient as well. By having these methods, communities that cannot afford these kits can have an accessible way to measure toxins in bodies of water.

To discover these results, Grover and Lin contacted a graduate student at Portland State University. From there, they also connected and shared their findings with the United States Geological Survey and the Oregon Health Authority.

“These people have advised us on a project and were also people we could share our results with, and in hopes that it might actually help them with their research,” Grover said. “And that was really amazing how our scientific research can have a broader impact on the community.”