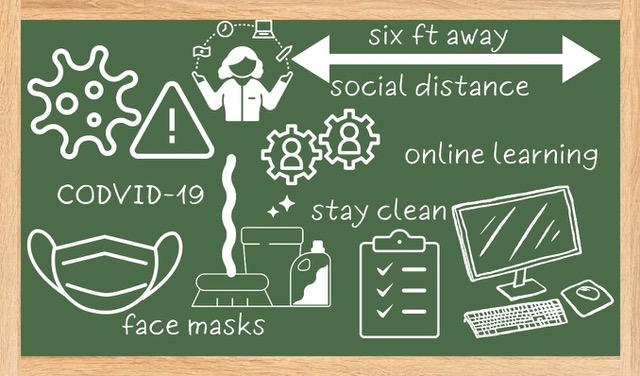

School closures and transitioning to online and hybrid learning have affected the social and educational outcomes for primary students. COVID-19 served as a starting point for immense academic loss for elementary students, taking away developmental school years.

Though COVID-19 first occurred nearly four years ago, students being taught from kindergarten to fifth grade have been arguably hit the hardest, due to a lack of development commonly gained in those years.

Behind the problem

The Oregon Department of Education declared that K-8 grades must maintain at least 900 hours of schooling scheduled per year, or at least 180 days fulfilled. Worldwide, as many as one billion students lost a full year of in-person learning because of the closures of schools. In low-income countries, this resulted in 70% of 10-year-olds having the inability to comprehend simple text.

Initially, schools would reopen after two weeks in quarantine to prevent cases from spreading, but the decision was revised as COVID-19 tests continuously came back positive. Just over one-third of the 2019-2020 school year was lost, with schools having to adapt to remote teaching and learning so each student had an accessible learning structure.

Vanessa Cochran, fourth-grade teacher, has been teaching for 22 years, with five of them being in the West Linn-Wilsonvile School District. Currently, Cochran is teaching fourth-graders at Boeckman Creek Elementary but has taught multiple age groups in the past. For Cochran, quarantine was partially used to learn various teaching methods to ensure a proper schooling method.

“We started [online learning] when we shut down after spring break, but not live with students,” Cochran said. “We would post assignments and they would complete them as best as they could.”

The first months of COVID-19 stood as an opportunity for districts and their navigation toward an accessible learning environment. Zoom, an online communication platform, was widely used in 2020, but was not originally a central part of schooling. The new technology proved difficult for some teachers to adapt to with little instruction, and for students who didn’t have the materials needed for hybrid learning.

“Later on, we were given the ability to go on Zoom, which we would do every day from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m.,” Cochran said. “Then we had 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. to correct assignments and give feedback to students.”

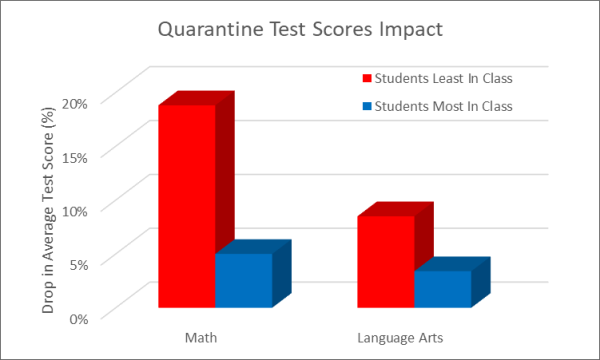

The Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond found that students with the least time spent in the classroom during quarantine saw their average test scores drop by 18.8% in math, and 8.6% in language arts. Students with the most attended school hours only saw test scores drop by 5% and 3.4%.

In the 2020-2021 school year, the district had students on an A-B schedule, which had students and staff attend in-person learning half of the week and were online the other half. However, some students had a different experience.

“A few students coming in on both of those days were students who were impacted severely,” Cochran said. “So maybe [this includes] students with special needs or someone who had a severe impact of being at home.”

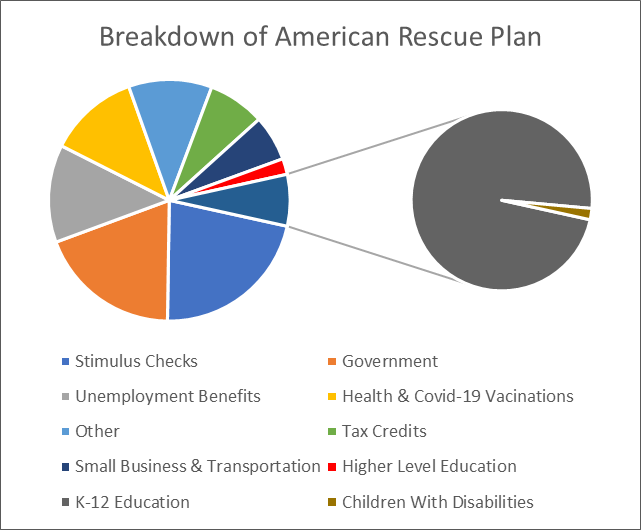

Students with disabilities, or specific and significant needs, were challenged academically and educationally impacted more than any other group of individuals. The 2021 American Rescue Plan was signed into law by the Biden Administration, costing 1.9 trillion dollars. The bill consisted of funding adults with unemployment benefits, COVID-19 response, and rental assistance for housing. The bill also financed 130 billion dollars in K-12 education, but only 2% of the money was used to fund children under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Constructing creativity to combat shortcomings

Heather Johnston, grade school counselor, has worked with students for 10 years, but started working at Riverdale Grade School at the start of COVID-19. Johnston was on Zoom full-time, working with K-8 children on social and emotional topics.

“I had to get very creative,” Johnston said. “At the elementary level, I would dress up as ‘Inside Out’ characters, whatever I could do to get them excited.”

Working with nine different grades, Johnston continued to find social and emotional patterns across the school. According to NLM.com, 14% of parents reported their children had worse behavior during COVID-19 than before.

“We are seeing the gap in strong communication skills,” Johnston said. “Kids don’t know how to communicate, or talk to somebody, or express their needs. There’s also a lack of engagement, with more focus and distractibility. We are seeing an increase of ADHD diagnoses because of the increase in screens, and the reliability kids have on technology.”

There has also been a recorded change in children’s emotional health, rooting from the effect COVID-19 has had on families. According to Frontiers, there has been an increase in stress, depression, and anxiety among kids, resulting in a 17-27% increase in emotional difficulties.

“Students are a lot less mature than they were,” Cochran said. “I noticed that students have a limited capacity for when things don’t go exactly as planned. I can see fourth-graders who are exhibiting more of a second-grade type behavior in dealing with other people.”

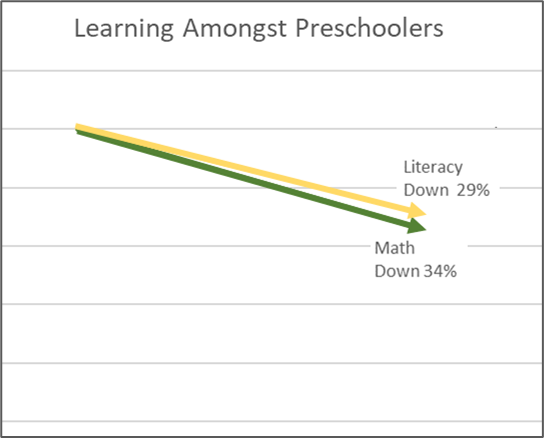

The same patterns are found academically with students struggling with their coursework. World Bank found that preschoolers across the world have decreased their abilities educationally, and lost more than 34% of learning in math and 29% in literacy.

“I’m seeing students who are severely behind in reading, and students who are behind in math who do not have the ability to do basic adding and subtracting with manipulatives,” Cochran said. “They don’t have those concepts really concrete in their brain, and then when they move on to harder concepts, this hole is pretty obvious that they didn’t get that significant ability.”

Incoming infantilism

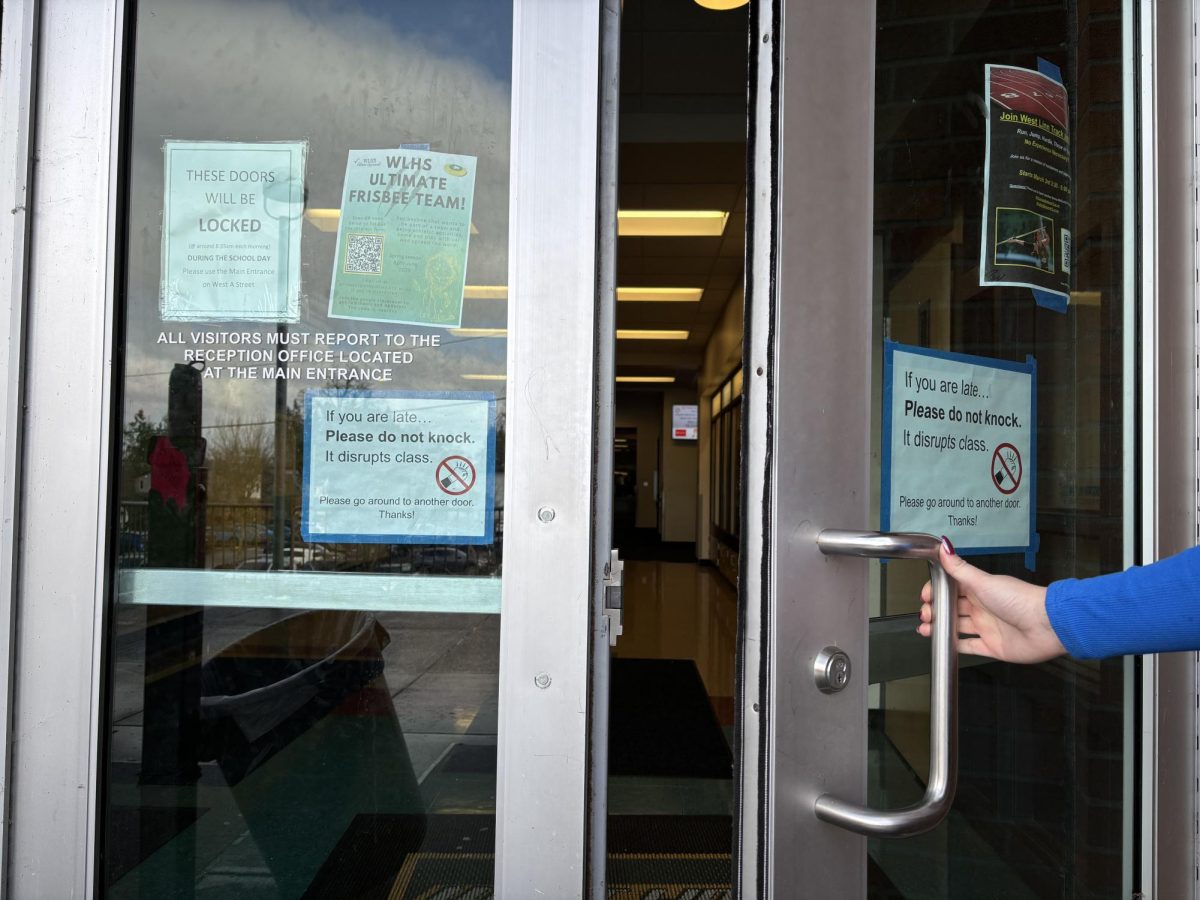

As years progress past the pandemic, elementary and middle school students who were in their central years of development when the pandemic began are now venturing into high school. Currently high school educators are having to find ways to correctly adjust to the younger grades.

Meagyn Karmakar, ninth grade assistant principal, has been working as an educator for 24 years, consecutively all at West Linn High School. While Karmakar taught as a language arts teacher during COVID-19, she presently works from a leadership position as one of the school’s six principals.

Having a wide viewpoint as an instructor, Karmakar has seen numerous changes through students and each grade level.

“Each class is slightly different, it depends on what they missed.” Karmakar said. “Ninth graders were hit during their fifth grade year, so their sixth was online. So their skill set, and that transition from fifth to sixth was weak and missing. We’re starting to see a little bit of that struggle here.”

The school is seeing continuing patterns in multiple areas including academically, but social effects have been impacted as well.

“A big thing we’re seeing is the struggle to transition.” Karmakar said. “We didn’t get to see the behavioral concerns, because they weren’t in school for us to catch those things and give early support. And of course the socialization is huge, because the kids are different. The world is changing so much, and it’s changed our outlook of reality, so students are different emotionally than they have been before, and that takes adults a lot of adjustment too.”

Looking ahead

Kids still have time to modify and develop to the place where they need to be academically and emotionally, which is the only solution to the problem at the moment.

“It’s just gonna take a lot of people keeping their eyes on the youth,” Johnston said. “Working through all of the mental health factors because of isolation and not being able to communicate, a lot of kids are holding it in, or just not being present.

COVID-19 has made kids adapt and learn while not in school, but there is belief that students can face this adversity.

“I think part of [the solution] is just going to be time and exposure back to people in school,” Cochran said. “I think we’ve learned a few things about how children learn during this experiment of online learning. It’s really the in-person learning that makes such a big difference.”

While it’s unknown how long the post pandemic issues will progress for, the high school is already trying to slow the process down, and acknowledge its presence.

“One of the things we’ve talked about is going back and doing direct instruction that we haven’t done in the past.” Karmakar said. “It’s really important that we stay flexible with students as we want them to succeed. If kids need to take a break, or redo something that’s totally fine. We’ll continue to change and acknowledge each class is going to be slightly different, coming from different contexts.”

![Reaching out. Christopher Lesh, student at Central Catholic High School, serves ice cream during the event on March 2, 2025, at the Portland waterfront. Central Catholic was just one of the schools that sent student volunteers out to cook, prepare, dish, and serve food. Interact club’s co-president Rachel Gerber, junior, plated the food during the event. “I like how direct the contact is,” Gerber said. “You’re there [and] you’re just doing something good. It’s simple, it’s easy, you can feel good about it.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/interact-1-edited-1200x744.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)