Controversy over banning ‘Maus’, a graphic novel about the Holocaust

Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer prize-winning work from 35 years ago now banned in Tenn.

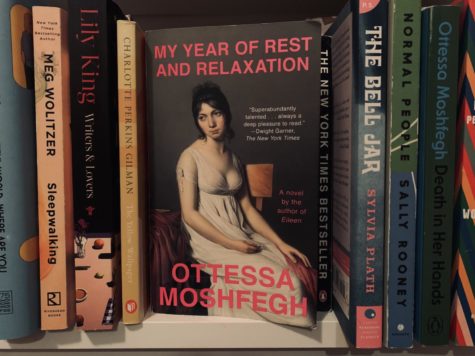

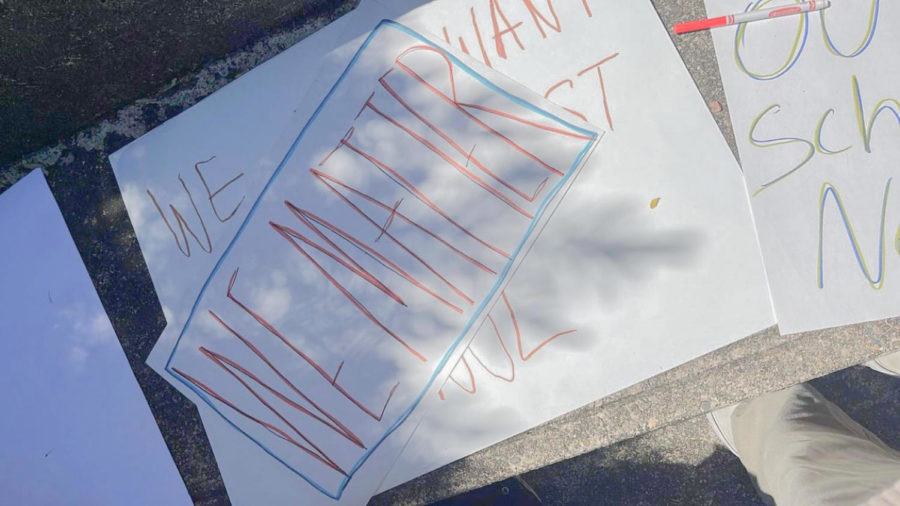

Raising questions about conservative censorship trends in books and public education, banned lists with titles such as “The Hate U Give”, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings”, and “The Color Purple” now include “Maus” in their ranks.

In Jan., a Tenn. school board banned “Maus”, a graphic novel about the Holocaust, from school curriculum, claiming that their reasons had to do with the book’s use of profanity and nudity.

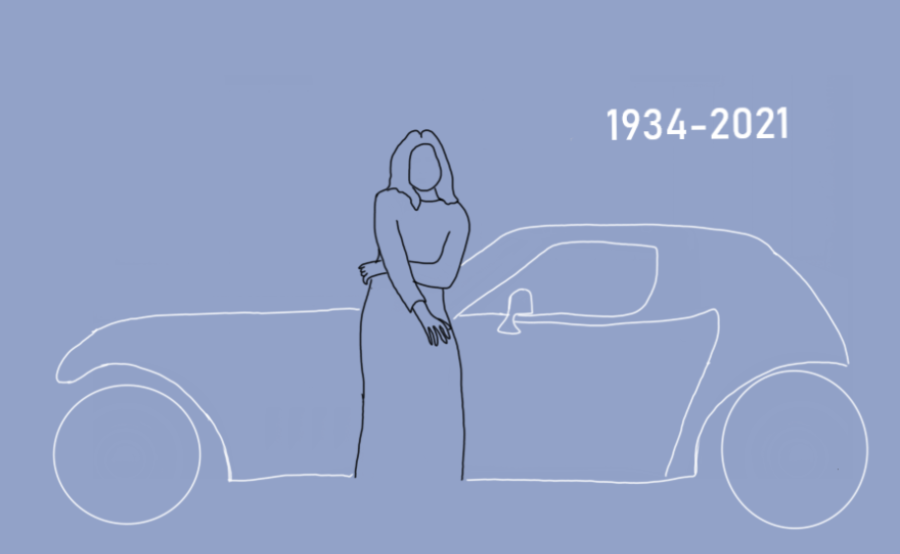

Art Spiegelman’s novel, first published in 1986, followed by a second volume in 1991, is a raw, truthful depiction of the Holocaust through the experiences of his Polish Jewish parents, who survived Auschwitz.

In his drawings, the Jews are mice and the Nazis are cats, playing off of antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish people as pests, and the racial hierarchy seen by the Nazis.

“[I thought], ‘All right, I’ll do something about racism in America with Ku Klux cats and mice.’ And I started climbing that black hole until I realized that I just didn’t know enough to be able to do it properly,” Spiegelman said in a 2011 interview with NPR, discussing the creation of the metaphor.

“And then a whole other flood of images came to my mind, ranging from “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk”, a story by [Franz] Kafka in which there’s a kind of way of reading it where it seems that the mouse folk are the Jews. There’s the image more basically that Hitler used of the Jews as the vermin of mankind that had to be exterminated,” he said. “The mouse metaphor allowed me to universalise, to depict something that was too profane to depict in a more realistic way.”

Volume I, “My Father Bleeds History”, recounts Spiegelman’sfather, Vladek’s, and his mother, Anja’s, lives from the mid-1930s to winter of 1944.

Vladek as a young man falls in love, has a child, succeeds in business in a well-to-do Eastern European family, and watches as every establishment of his thought way of life—the way of general humanity—is left broken by hatred, violence, and betrayal.

Spiegelman’s work is a bold declaration of truth and history, demanding of you to question why you think any part of his storytelling is bold. An organically unapologetic reframing of how we as the public remember the horrific events of the Holocaust, “Maus” delicately holds the relationship of a father and son in its hands, whispering clearly and solemnly the ultimate tragedy of the few survivors and the causations of the greater majority that were lost; and even more unspoken is the distance between Art and Vladek in older age, having lost their mother and wife to suicide.

Beautifully frank in the telling of Spiegelman’s relationship with his father, a restoration of humanity—not as the general greatness of the thing, but instead its realness—make your hands hover over your chest to check if your heart hasn’t sunk to your toes, or left your body completely.

You forget to breathe until the last page taunts you with its ending—understanding only then how much the second volume is craved and needed.

Why then, would such a moving, accurate graphic novel on one of the most devastating events in history, be banned from schools?

When it came to the unanimous vote of the ten-person board in McMill County, many questioned its validity in reason. Many books still being taught are graphic in language and content, so why would “Maus” be an exception?

Many have recognized growing anti-semitic sentiment over the past years, and wonder if similar trends of banning books about sex, Black, Latino, or LGBTQ+ characters have added “Maus” to the list.

Despite country outrage and confusion, those in Tenn. remained committed to their position. Mike Cochran, one of the ten members, took issue with the book’s language and nudity.

“We don’t need this stuff to teach kids history,” Cochran said. The board issued a statement saying the book was “too adult-oriented” for students, but in its place, there was no clear replacement for “Maus”.

This raises the question: is there a replacement for what “Maus” covers? With first hand accounts from Auschwitz, the lives of survivors, and the lives of their children, family, community, “Maus” serves simultaneously as a memorial and a museum.

Spiegelman himself expressed confusion and frustration after reading the minutes from the meeting.

“This is disturbing imagery. But you know what? It’s disturbing history,” he said in an interview on Holocaust Remembrance Day. He thought the school board wanted to teach a “nicer Holocaust”.

Want to get in on the action? Not banned in Ore., you can find a copy of “Maus” at the school library or at the West Linn Public Library. In all of the fray, demand for “Maus” has risen significantly, rising to the top of Amazon’s bestseller list in Jan.. (In writing this piece, I was able to read the first volume, however the complete work was out of stock and in circulation.)

The ruling in Tenn., while raising questions about school censorship, antisemitism, and conservative waves of book banning, has shown the country the importance of educating students about the Holocaust.

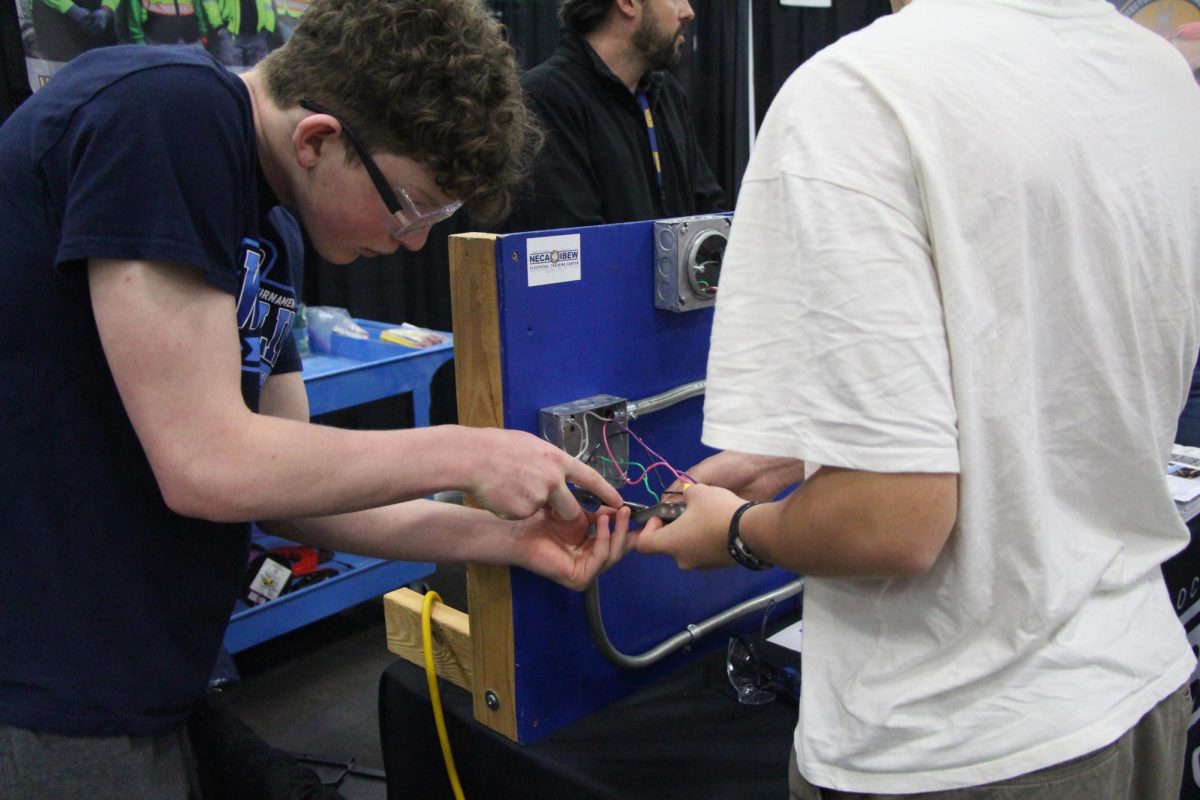

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Myrtle Guarisco, sophomore, is the Opinions Editor for wlhsNOW.com, and finds writing to be an incredibly expressive way of informing the public about...

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)