Mass shootings define our generation

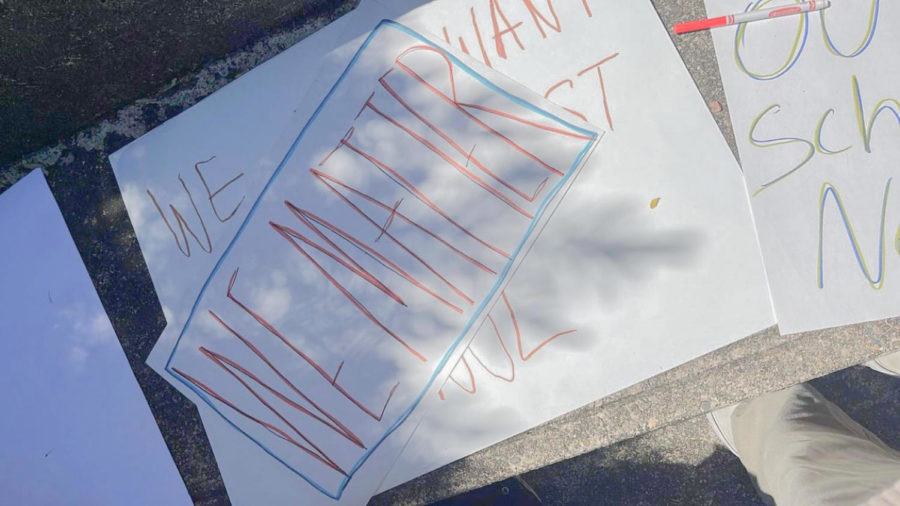

There has been yet another school shooting. This time in Santa Fe, Texas.

It all feels so familiar. The scene. The victims. The parade of news reports. The vigils and the names take on the dull hue of an endless procession.

So familiar is it, indeed, that it has become almost a part of the schooling tradition. Students go to class every day, to take tests and give speeches, to straggle in the hallways and laugh with friends. To go through the motions of childhood. They prepare for prom and graduation. And every two months or so, a dozen of them are brutally murdered.

It’s hard to remember a time before all this. Of course, I can’t. Not really. My class is, so famously, the first born post-Columbine.

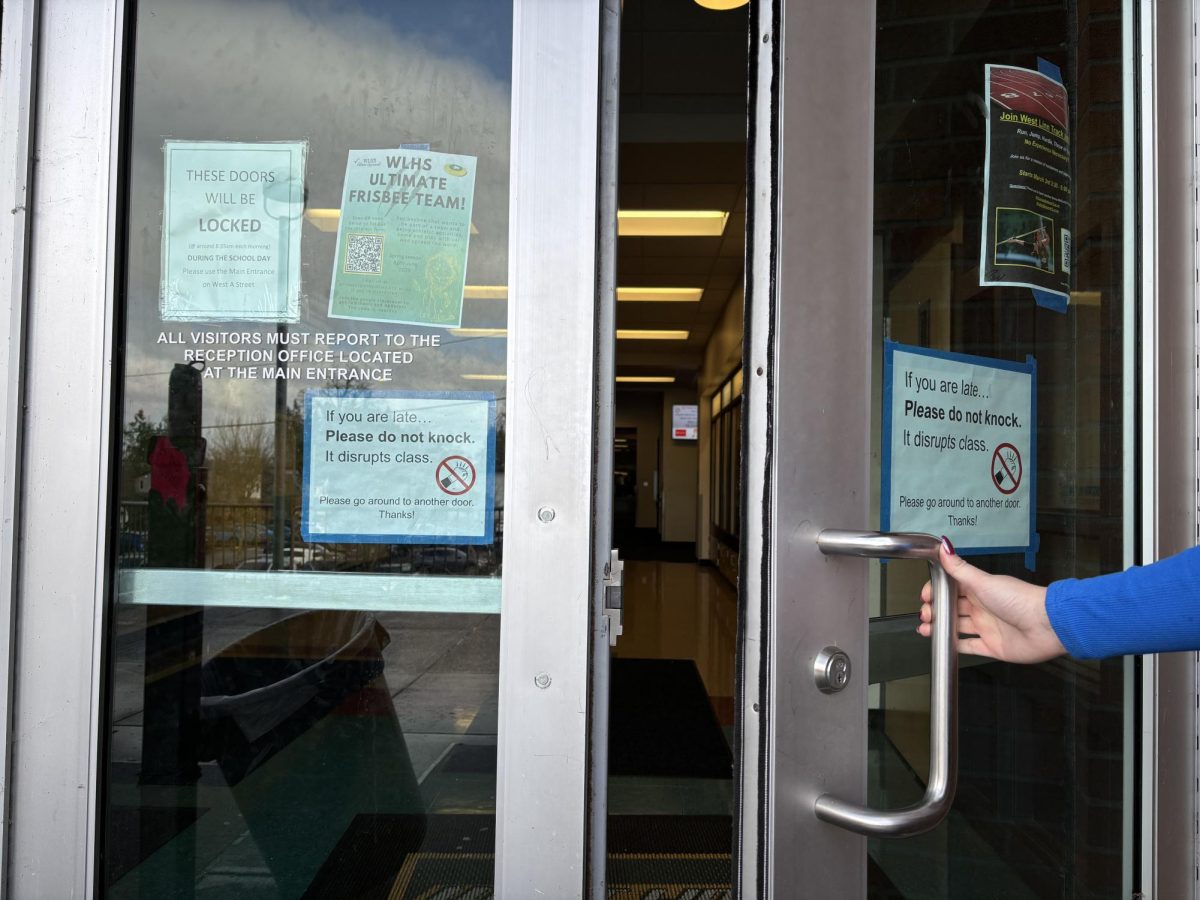

But I do remember a time of relative peace. My elementary school days came in a different era. My campus was open. Students walked outside to get from class to class. No one talked about shootings. We never practiced lockdown drills. We were children. We never thought we would die. We never thought about dying at all. It was foreign to us. We think about dying a lot now.

I drove past my elementary school yesterday. There’s now a massive black fence around it. The kind you’d see at a military base. I guess that means they’re thinking about dying too.

After the shooting in Parkland, Elizabeth Bruenig of The Washington Post wrote “Every time we rehearse again the motions that follow the destruction of young lives, millennial cynicism looks more like simple reason.” Watching my childhood playground walled off to keep first graders out of reach of AR-15’s, it’s hard to argue.

It’s a cynicism best encapsulated by Santa Fe student Paige Curry, who explained to a local news station “It’s been happening everywhere. I’ve always felt it would eventually happen here.”

That conclusion, too, is hard to write off. I’ve spent the last few days frantically wracking my mind, looking for any reason why a shooting would not happen at my school. I can’t find one.

Few members of my generation live in constant fear of shootings. How could we? To suffer through school every day would become unbearable, and besides, the reality is that these events are incredibly rare, at least when compared to the number of schools and students in our nation.

But the possibility does exist. I’m not safe at my school. I know this. If, god forbid, a maniac ever had access to weaponry and the desire to kill me and my classmates, I know as well as anyone else does that they would succeed.

This is what it means to be a student in 2018. The constant understanding that the only thing between you and the barrel of a gun is whatever frail bonds hold human sanity intact. And the irrepressible knowledge that someday, somewhere, for someone, those binds will snap.

I cannot help but wonder what sort of toll this takes on people. It’s hard to think of a comparable situation in modern American history. Even the threat of being drafted into a war retained at least the possibility of escape. A retention of some small vestige of personal agency. If a shooter ever does come to my school, I will simply have to cower in the dark and hope his sights are aimed elsewhere.

It’s a morbid subject, but it’s not exactly one we can ignore. And so it seeps into conversation in odd ways. Often, as a sort of gallows humor. We’ll joke about who might be the next shooter. Sometimes it appears in the form of arguments. Students are not the united front they are presented as on TV, and fiery debates about gun control and Second Amendment rights are common. Sometimes it’s almost a bizarre form of small talk. “Did you hear there was another school shooting?” Like you might talk about the weather or a sports game.

Whatever the context, the surface-level recognition is simply one facet of a crushing and constant presence, hanging, like the sword of Damocles, above a whole generation of children.

Shootings have simply become a fact of student life. We go to school. We learn to read, to write, and where best to hide from bullets. One day we practice presenting essays and taking tests, the next, crowding into corners and staying silent.

These are the experiences that shape people. The stories and the thoughts and the fears that make up society and culture. Each shooting becomes a part of us. Each killing is another thread in the fabric of our humanity.

I wish I could offer up conclusions. I wish I could say that this trauma would make us stronger or weaker, that this fear would make us hopeful or hateful. But the truth is, I have no idea. I’m in the dark as to what this means. We all are. Only time will tell what impact these massacres have on us. All anyone’s knows is that this is who we are. We are the killers and we are the dead. We are the victims and the protesters. Every bullet seals the verdict: we are the mass shooting generation.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Andrea Secchi is an award-winning portrait, fashion and lifestyle photographer from Portland, Oregon. Her love of sharing people's stories lead her...

![Reaching out. Christopher Lesh, student at Central Catholic High School, serves ice cream during the event on March 2, 2025, at the Portland waterfront. Central Catholic was just one of the schools that sent student volunteers out to cook, prepare, dish, and serve food. Interact club’s co-president Rachel Gerber, junior, plated the food during the event. “I like how direct the contact is,” Gerber said. “You’re there [and] you’re just doing something good. It’s simple, it’s easy, you can feel good about it.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/interact-1-edited-1200x744.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)