Reimagining high school

An analysis of secondary options to fulfill graduation requirements

Regardless of how many class periods a district offers, the number of credits requited to earn a diploma in Oregon remains: 24.

24: the number of credits needed to graduate. 24: the number of classes offered for a full-time student over the four years of high school. However, students are breaking out of their six-period constraints, with 380 enrolled in an early period, 229 in a late period, and in a 257 in a summer school course as of the 2018-2019 school year. This is to say, many students are thinking outside of the box in order to walk across the stage in their cap and gown.

“There are some challenges students face with getting in their necessary courses within the periods 1-6,” Paul Hanson, assistant principal, said.

Currently, in order to graduate, students need four language arts credits, three math credits, three science credits, three social science credits, one health education credit, one physical education credit, three art, world language, or Career and Technical Education credits, and six elective credits to earn their diploma. That, of course, doesn’t include the specific credit requirements of any college they may want to attend.

Hanson has experience working at Liberty High School and notes the scheduling differences with the same number of credits required to graduate.

“Having come [from] an eight-period school, I kind of was like, ‘Woah, where do the kids fit all these things?’” Hanson said. “And that’s where I saw that the offerings here for early bird were far more than I had seen in other high schools.”

So, why is the six-period model in use? Todd Jones, history and US government teacher, breaks it down.

“[An] advantage, to be quite honest with you, to a six-period day, is a financial advantage for the district,” Jones said. “Right now, we have a six-period day, and each teacher teaches five of six, right? You take five and divide it by six, and we all teach 83% of our contracted work.”

However, if the schedule changes, those figures shift.

“In an eight period day, teachers teach six of eight, right? So instead of teaching 83% of my day, I’m teaching 75% of a day. It helps the teacher, I have more planning time,” Jones said. “It does not help the district, they have teachers spending less time in front of kids, which means they have to hire more staff to provide that instruction time to the students they have. So, an eight-period schedule is a more expensive model.”

And where exactly would that funding come from? Well, the district would have a couple of options.

“They have to figure out if I don’t have that money, what am I going to do? Am I going to cut staff, or make class sizes larger, or how am I going to pay for a more expensive model?” Jones said.

However, there may be complications to solutions such as increasing class sizes. Hanson notes that West Linn High School is likely nearing maximum capacity, although plans for a new high school within the district are in the works, that would replace Art & Technology high school, as the property lease expires in three years.

“The plan right now would be to convert the property where Athey Creek is, and turning that into kind of a ‘choice’ high school that would serve grades 9-12, but would have a big focus on career and technical ed,” Hanson said.

The district would not be the only ones facing challenges in the event of a switch to an eight-period model. Students and teachers alike would have to adapt.

“One of the disadvantages for you as a student is, ‘I’ve literally got eight classes,’” Jones said. “That means ‘I have eight classes, I’ve got to keep track of eight classes I have homework for.’ That can get overwhelming for a student.”

Particularly, this change may impact underclassmen.

“One of the things that was really hard was that it was a very large adjustment, particularly for ninth graders,” Hanson said. “[They’re] going from having six teachers and seeing them every day to having eight teachers and seeing them rotating days.”

“Also in regard to students getting the hang of high school,” Jones said, “it makes it hard for students to feel like ‘I’m on top of my material’, it’s harder to establish relationships with teachers, it interferes with a continuity of material.”

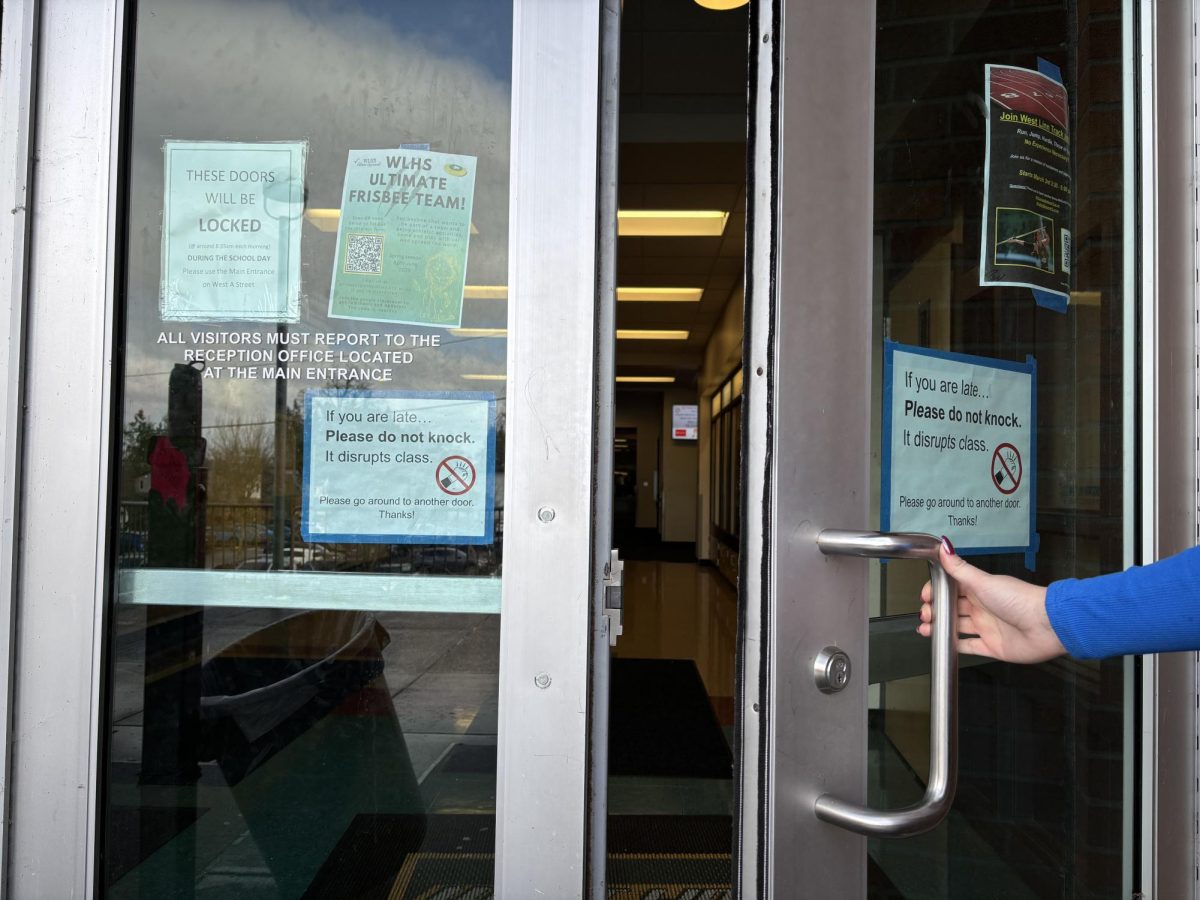

The existing schedule is in place, to avoid these challenges. However, supplementary classes, such as early, late, and summer courses, come with barriers greater than the longer school day. A “Go Ahead” course, or summer class, comes with a $100 price tag, and the school does not offer transportation to before-school classes.

“If a student of means, that can afford to do this, says, ‘I’m going to take an online class and pay for it’, the operative word there is ‘pay for it’. Not everyone in our community can afford to pay for all these extras, or have mom and dad have the transportation to get me out early and late,” Jones said. “It’s a question of fairness to put our students in a position to feel like they have to do stuff outside of their 8:30-3:10 day.”

That being said, the district has made an effort to make these courses more available.

“I think conversations have been brought up about examining early period, and maybe taking more of a look at late period, because we do have transportation available with the activity bus,” Hanson said. “We want to make sure we aren’t putting up any specific barriers for kids to attend, that’s why we have some of those scholarships available.”

So, as West Linn high school nears capacity, and the lease on Art Tech expires, there is no shortage of opportunity for the district to re-examine the way learning is structured. But there may be a shortage on budget. Any schedule model comes with unique opportunities, as well as challenges, as Jones notes.

“There’s no perfect schedule,” Jones said. “But what I think we should do, in my opinion, in this district, is at least explore the options. Because we force students to either do without any kind of choice or find ways to fit in all this stuff just to graduate. It really comes down to an equity issue.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Matilda Milner, senior, has been on the wlhsNOW staff since the first day of her freshman year of high school. Rising through the ranks, she has now arrived...

A nationally award-winning photojournalist, a board member with West Linn united, and fluent in Japanese, Gigi Schweitzer is more than just the Editor-in-Chief...

![Reaching out. Christopher Lesh, student at Central Catholic High School, serves ice cream during the event on March 2, 2025, at the Portland waterfront. Central Catholic was just one of the schools that sent student volunteers out to cook, prepare, dish, and serve food. Interact club’s co-president Rachel Gerber, junior, plated the food during the event. “I like how direct the contact is,” Gerber said. “You’re there [and] you’re just doing something good. It’s simple, it’s easy, you can feel good about it.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/interact-1-edited-1200x744.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)