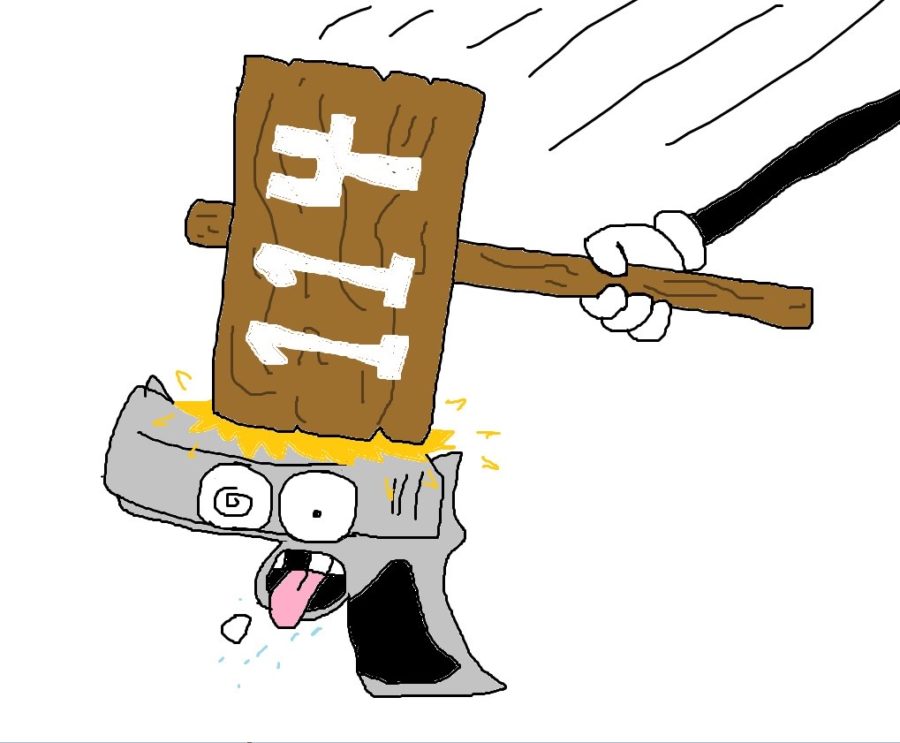

At the beginning of the school year, some students may have questions about how they will be graded in each of their classes. Grading practices have changed over time, depending on what teachers think is fair to their students.

Portland Public Schools (PPS) have created new practices in order to be equitable, according to KGW8. These include not giving out penalties for late assignments, no grades given below a 50%, and no late or missing work will earn a zero either.

Teachers and admin at the school have also noticed that giving out zeros is not necessarily helping students improve their grade or want to learn.

Last year, a 50% floor was implemented in order to make grading fair for all students. Students who struggled with a subject would no longer fall behind in class and have to make up what could be 40% of their grade in order to get a D.

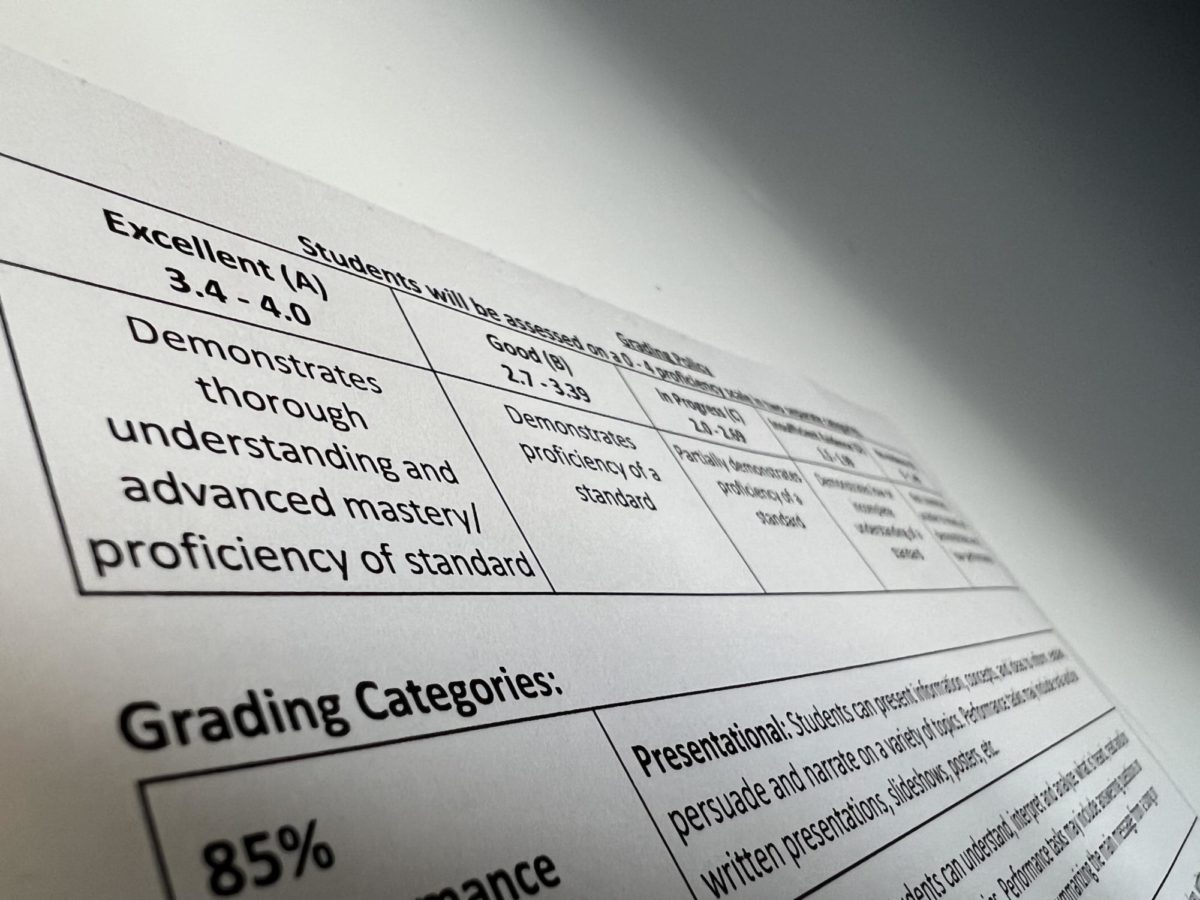

Similarly, some teachers at the school started using a new grading scale, one that ranges from one to four points. This scale was implemented for a similar reason: to help students recover from a failing grade.

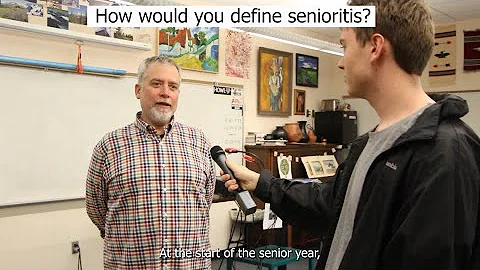

Michael Sugar, social studies teacher, has been teaching for 10 years, two of which have been at the school. Along with the rest of the history department, Sugar has been using the four-point grading system in his classes.

“I think it’s fairer,” Sugar said. “[And] a number of teachers in our department were already doing that, so it made sense to do what others were doing.”

This newer scale equates a one as around a 50-60%, or a D, and a 90-100% as a four and an A.

“I think [the four-point scale] is better for students if they are absent, [or] if they are struggling with a class and they did something and want to redo it,” Sugar said. “I think this approach favors building skills.”

While PPS has started using the equitable grading practices, only some teachers at West Linn are using the four-point scale, and it is not a schoolwide policy. This is for a variety of reasons, one of which being that it might make Advanced Placement (AP) classes more confusing.

“I’ve heard suggestions that the four-point scale doesn’t make as much sense for AP, and the way AP is scored,” Sugar said. “Having taught AP, I can see that reasoning.”

Sugar acknowledges that students may have a different perspective on the grading scales, and how they benefit from each.

“I would be curious what students think,” Sugar said. “And I haven’t really asked other departments at an extraordinary level, apart from random conversation.”

As for AP classes, Miranda Portilla, junior, believes that the four-point scale can actually be more beneficial for grading.

“I think [the four-point scale] is very helpful,” Portilla said. “Sometimes it gives you like, a built in curve. With AP classes usually that happens anyways, but it always depends on what everyone else gets. I took [AP United States History] last year and there was always a curve, but sometimes it would only be like, one point. And honestly, that doesn’t really help.”

Jacob Kemp, junior, has experience with both the traditional percentage scale and the four-point scale, but prefers the latter.

“I love it way more,” Kemp said. “It’s easier for me to be able to look at the rubric and the expectations under the four-point system. 100 is kind of a big number, so it looks a little scarier. I think one through four kind of makes it less scary and less stressful.”

The four-point scale can be applied differently to certain subjects. Some classes, such as Spanish, already use a rubric system with four levels of criteria for students to meet. Hunter Parrish, junior, is taking a Spanish class that uses four-point rubrics.

“For Spanish it’s really good because [of] the four categories you need to be in to get that grade,” Parrish said. “For math based classes, it’s not as helpful because it isn’t as specific as what it should be, especially on assessments.”

One potential issue with having two different systems is that the school becomes divided. Students have eight classes now, and their teachers are using different scales. A schoolwide policy could be implemented in order to standardize grading, but it might also disturb what teachers and students are comfortable with.

“I feel like if they do make a policy, it should just apply to certain departments instead of the entire school,” Parrish said. “Math-based classes would be harder to get [a policy] to work, while say history or language, it’d be easier to use for those because it’s easier to set out requirements for each one.”

It’s possible that a compromise will be made between the two scales, or an entirely new system will be created in the next few years. But for now, the grading scale will be determined by the individual teacher.

![Reaching out. Christopher Lesh, student at Central Catholic High School, serves ice cream during the event on March 2, 2025, at the Portland waterfront. Central Catholic was just one of the schools that sent student volunteers out to cook, prepare, dish, and serve food. Interact club’s co-president Rachel Gerber, junior, plated the food during the event. “I like how direct the contact is,” Gerber said. “You’re there [and] you’re just doing something good. It’s simple, it’s easy, you can feel good about it.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/interact-1-edited-1200x744.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)