‘Grading for Equity’

What it means and how it impacts students.

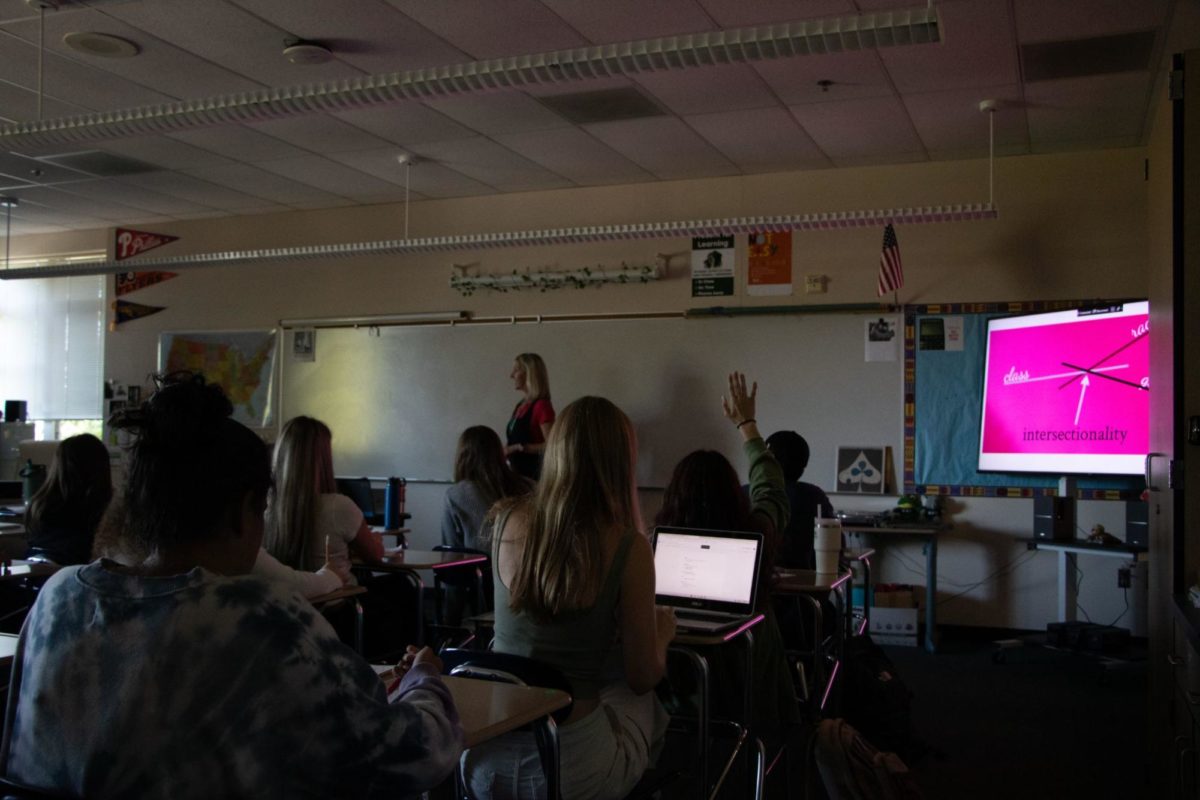

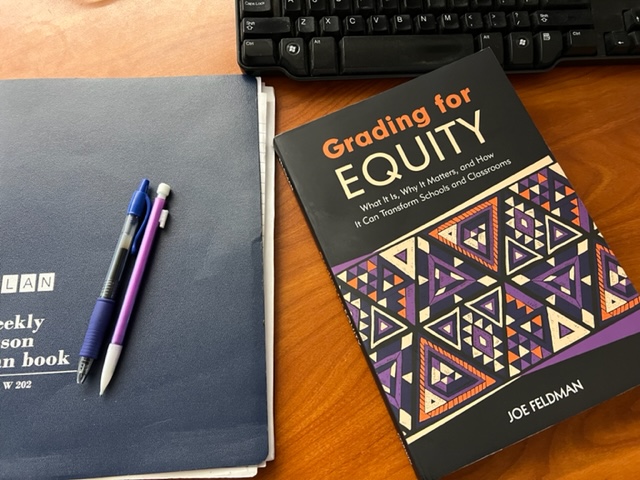

At the beginning of the 2021-2022 school year, teachers were given “Grading for Equity” and encouraged to use its lessons in their own classes.

Going into the 2022-2023 school year, students and teachers were likely anticipating a year different from any other. It was the first school year since 2019 that began in a typical fashion— late Aug., no masks, in-person classes, etc.

The actual differences this school year occurred at the administrative level. Lunch has been shortened by five minutes to accommodate the school day that ends at 3:05 rather than 3:10, students are now offered time to say the pledge of allegiance, and a new grading system has been implemented.

The “Grading for Equity” system is modeled after a book of the same name, written by Joe Feldman.

“Grading practices are a mirror not only for students but also for us as their teachers,” Feldman writes. In addition to publicly speaking about his book since 2018, Feldman has been working with teachers nationwide for the past couple of years to train them in this grading model.

Jennifer Howe, biology and chemistry teacher, was amongst a group of teachers who were personally trained by Feldman last school year. Through the training, Howe was made aware of the changes she wanted to make and began implementing them last school year.

“There was a book study the spring before last [school] year so I’ve been doing it now for about a year and a half,” Howe said. “[Feldman] led us through a whole year’s worth of professional development, so we would collect data and then meet quarterly and strategize.”

As another teacher trained by Feldman, Meagyn Karmakar has witnessed this shift take place as an English teacher and in her new role as the Academic Success Coordinator.

“I found students less stressed,” Karmakar said. “You know if you’ve shown me your skill, great, but life gets in the way sometimes.”

One significant change is that students are no longer provided the opportunity to receive extra credit. Instead, teachers are expected to provide students the opportunity to revise their work if it does not meet expectations.

“Extra credit is actually not bias resistant,” Karmakar said. “There’s all kinds of things that would impede someone from being able to do [extra credit]. And so, by doing it I’m not showing you a skill I’m showing you I can follow directions.”

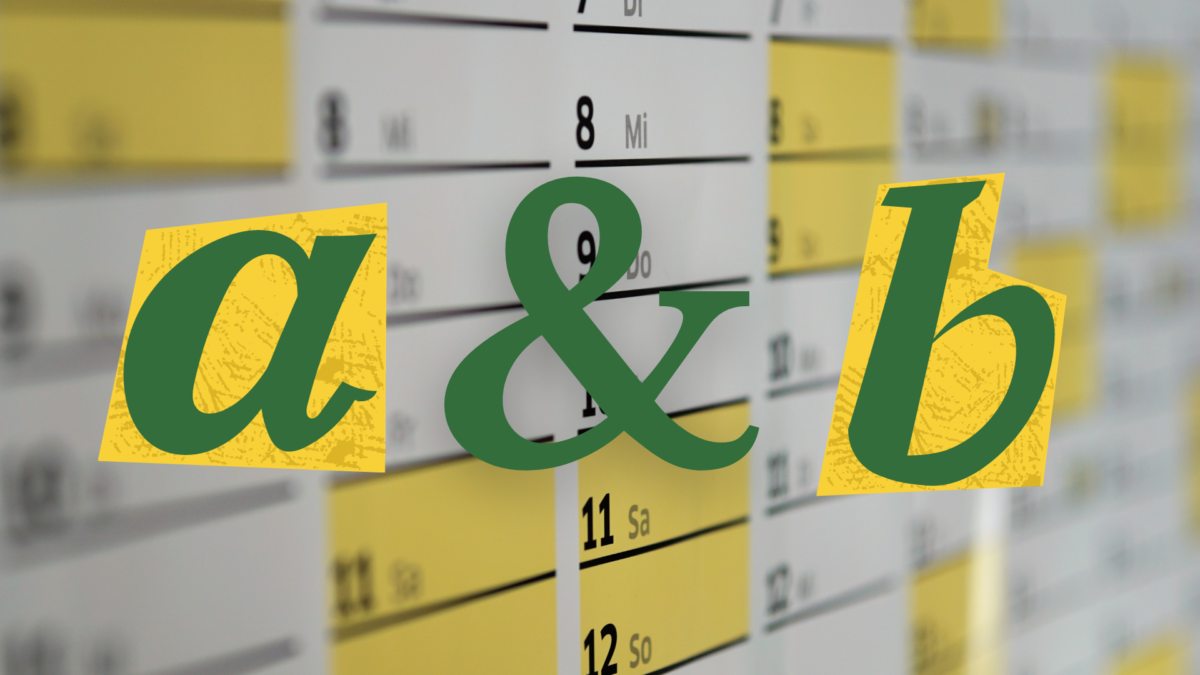

Additionally, a 50% floor has been implemented for all grades. What does this mean?

Previously, students were graded on a 100-point scale in which anywhere from 90-100% is an A, 80-89% is a B, 70-79% a C, and 60-69% a D. This then meant that an F could be made up of anywhere in the 0-59% scale. By implementing a 50% floor, an F exists only on a 50-59% scale.

“I started doing [the floor] a couple of years ago just to see what it did,” Howe said. “The reality is it only impacted the students at the very bottom and it just gave them a bit of hope, and there was a more clear pathway to passing than there was before, so I found that really promising.”

Ultimately, the changes made under this model attempt to divide grades into two categories: academic and behavioral. Academic grades refer to test scores, projects, and class assignments while behavioral grades refer to the completion of homework assignments, class participation, and peer interactions. The next step from here is to entirely erase behavior-specific grades, as they are seen by Feldman as subjective and therefore more susceptible to bias.

“Although some subjectivity may exist in evaluating academic categories like tests and projects, it is nothing compared to the significant subjectivity of evaluating these nonacademic categories,” Feldman writes. “…each teacher measures a student’s demonstration of those behaviors through a deeply flawed lens: the teachers’ observations of a student’s behaviors.”

Since it is early in the school year, it remains to be seen how this newly implemented system impacts students and teachers. As someone who has been implementing this change for years prior, Howe is hopeful that it will succeed.

“To me, the whole grading for equity [model] really means the idea of letting go of this one singular pathway to success,” Howe said. “It’s really freeing to do that.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Lily Gottschling, senior, is the Copy Editor-in-Chief for wlhsNOW.com. She loves writing reviews, features, and opinions. She is also a co-host of the...

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)