Where to draw the line

After reading the novel “Round House” students have questioned novel censorship in required literature

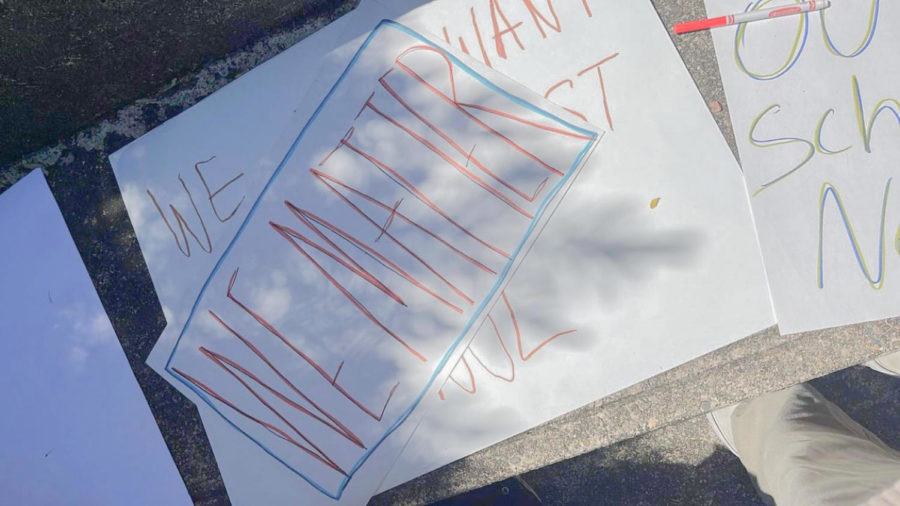

While sophomores begin to move past one of the optional novels in their newest unit, “Round House” continues to spark controversy for students wishing they were given some warning over the content- if not for themselves, for the safety of other students. “Warnings are crucial and should be included for books that have mature themes,” Kaelyn Cahill, sophomore, said. “This includes themes such as rape, abuse, NSFW themes, strong explicit language, homophobia or anything that could harm a student’s mental health.”

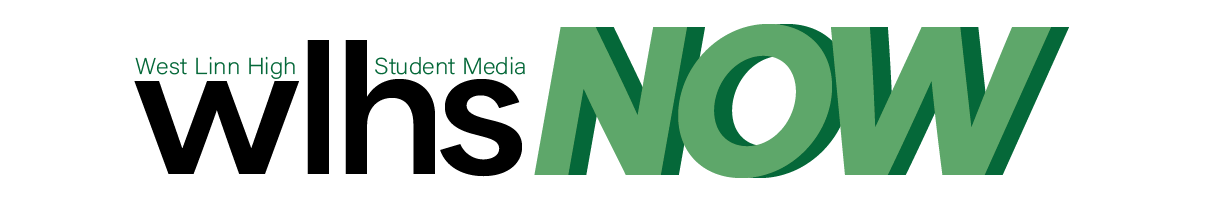

While everyone may love (or hate) their required English class, there has always been a constant in curriculums and mandated activity from teachers- required reading. If students find themselves lucky enough, they may sometimes be given the option to choose between a plethora of books based on the newest unit.

What makes some of these books warranted for a lengthy permission slip listing every explicit detail (and punctuated by a needed parent signature) while others remain overlooked? After beginning to read “Round House” by Louise Erdrich, students have started asking this question.

“There were a lot of sexual themes and descriptions of nudity in the book,” Kaelyn Cahill, sophomore, said, “much more than one would expect for a book that is part of a school curriculum.”

Cahill began reading the book after they were able to choose from three different books offered in their English class. After being given a brief summary of the novel, they decided to read the book.

“I started reading the book mainly because a friend of mine was reading it,” Cahill said. “I wasn’t there the day everyone talked about the book choices so I was choosing really just because of my friend.”

Before Cahill chose the book, they learned about the most graphic content from their teacher.

“I was aware there were mentions of rape in the book,” Cahill said “but not about the explicit use of language, depictions of abuse and mentions of sexual experiences.”

Other students, who were also informed about some of the content, felt slightly uncomfortable with many storylines and themes in the novel, including the societal implications projected onto the main characters.

“Through the whole book, the main character objectifies his aunt, who’s related to him through marriage, to the point where he blackmails her into giving him a strip tease,” Syndney Steinberg, sophomore, said. “This was pretty disturbing, especially because it was the protagonist doing it. A lot of the time this kind of behavior was just played off as ‘boys being boys.’”

Whilst other students remained shocked after continuing to read the book, and seeing content they did not expect, others remained otherwise unphased during the reading, and even appreciated what they perceived to be the main message of the novel.

“I thought it was an interesting book,” Jenny Yu, sophomore, said. “It provides an interesting perspective that I never thought about. Especially because I feel like we try to think there’s increasing acceptance in the world in many communities. I think that we’re looking at the positive side, but we fail to acknowledge that there’s still lots of unacceptable things going on. I feel like ‘Round House’ really tries to hone in on that side.”

Yu disagrees that the novel is inherently inappropriate unnecessarily, believing that even if it made others uncomfortable, it was an important part of the novel.

“I don’t think that’s something that should be going on in society, but it shows that the main character is dumb. It shows that in society people are influenced- and he’s influenced to be naturally inclined to feel this way even though he may not necessarily know why,” Yu said. “I feel like that is something people should know about. To me it’s not acceptable, but it shows people that this is going on and we need to do something to change it. Because kids don’t know why they feel that way, they just do.”

Regardless of the context, Cahill believes students that are uncomfortable should be able to stop reading, even if it means missing the perceived societal meaning in the scenes. Cahill highlighted this by referring to the strip scene, in which a 13 year old boy was present, as an example.

“While that part of the book served to teach the main character an important lesson,” Cahill said “it was still very uncomfortable.”

Yu believes that depending on the specific situation of the student, they should try to look at the passages with a critical eye to their everyday life since it can create crucial tools for critical thinking.

“If students are really uncomfortable with it I feel like they should talk to the teacher, but I think it’s fine that the teachers didn’t let the students know. I feel like as a sophomore you should be at a maturity level to just accept this as a fact, that they included this and it’s a mature aspect.” Yu said. “I think it’s necessary because it brings in an important aspect to what our society is really like, even if we don’t want to think about it like that and we don’t like to think of ourselves like that.”

Regardless of the content in the book, students both for and against the novel can agree that it’s not up for parents to decide that their children can or cannot read.

“From a student perspective. I think it needs a content warning but not a permission slip,” Steinberg said. “I think we’re at an age where we can judge for ourselves whether reading something will be too upsetting. Some parents might want a permission slip because there’s some seriously adult themes.”

Both Cahill and Yu had a similar statement, believing students novel choices should not be dictated by their parents.

“Personally, I am strongly against the idea that a student’s needs a permission slip to read a book for class,” Cahill said. “Parents shouldn’t be dictating what their children can and cannot read.”

While Yu had conflicting feelings towards parents intentions, she ultimately agreed, believing student freedoms should come before above all else.

“I feel like that’s something that’s necessary for younger students, but as a freshman or a sophomore it’s different,” Yu said. “I understand the point of a permission slip, but sooner or later I feel like parents should know that [students] are going to be seeing some content that’s not very clean.”

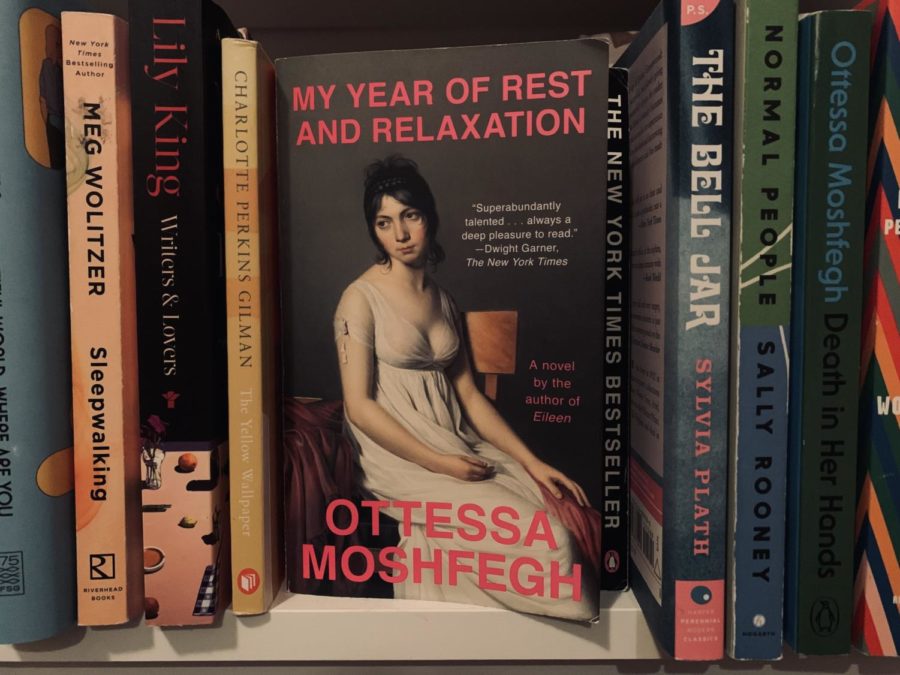

Regardless of content warnings or permission slips, many students also felt compelled to add the noticeably different treatments between this book and a novel read in students’ freshman year “Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe” by Benjamin Sáenz, which features two young men coming to terms with their sexual orientation and place in society.

“‘Aristotle and Dante’ is the only book that I was given a permission slip for,” Steinberg said. “It doesn’t make any sense to me. ‘Aristotle and Dante’ is a teen romance novel that happens to have gay characters, while the ‘Round House’ deals with explicit and unsettling topics. Any of the more adult themes they had in common were a hundred times more intense in ‘Round House.’”

Cahill, who voiced their confusion with the novel warning system after beginning to read the ‘Round House’, spoke up about this comparison early on, describing what they believe to be unfairness in the treatment of such novels.

“There is no reason ‘Aristotle and Dante’ should require a signed permission slip,” Cahill said. “The slip was probably put in place because it was a gay relationship which makes something that does not need to be an issue an issue. I believe that the book may have some slight drug use about minors, but so does the ‘Round House’, and that book had no permission slip.”

Alex Close, Language Arts department co-chair and 12th grade English teacher, states that his (or any teachers’) role doesn’t necessarily mean vetting the books through the school.

“I wouldn’t say that Ms. Murray and I are in charge of that. We’re usually involved in those discussions,” Close said. “The reality of it, though, is that almost all of the books that we teach here are district approved. They look at subject matter and the reading level, and they determine whether that book is appropriate for that level or not.”

Close stated that the approval of the district is a crucial part for teachers curriculum when it comes to preparing or dealing with any reaction from parents or others.

“Once a book is district approved there’s no real need for any kind of parental approval. It’s a district approved text and that’s what we fall back on.” Close said. “If a parent complains or raises a concern about a book that I’m teaching, then as a teacher I would respond with ‘I understand your concerns, here are some options, this is a district approved title.’ A teacher basically has some protection because the district has approved the novel. If I chose to teach something that wasn’t district approved then I would counteract that answer for that but I’m not aware of many teachers that teach books that aren’t district approved.”

While district approval is an important part of choosing novels, Close understood the confusion when asked why an additional permission slip is added for a book that has already been approved. Close began by describing the original intentions of more diverse novels such as ‘Aristotle and Dante’, as students such as Cahill and Steinberg described.

“I think to understand that you have to understand the context of the English Department in our district over the last four or five years. About five years ago there was a huge push in our district to diversify our English curriculum,” Close said “We were teaching a lot of traditional works what people thought of as the ‘dead white guys’ and so we sort of decided that we needed to modernize and diversify the voices that we’re representing,”

After choosing this novel, Close believed the English teachers were trying to switch to a more diverse mindset, and acted accordingly.

“For the last five years we been in a kind of been in a period of transition and when there’s a period of transition, especially around what some people see as controversial topics, there can be hiccups and friction, so I think that’s kind of what happened here and there,” Close said. “But last year what I think you’re really referring to is the Aristotle and Dante novel. I think there was some anticipation at concerns [regarding the novel] so the people [English teachers] involved wanted to send some sort of notification for why they were doing what they were doing. That ended up taking the form of a permission letter which was turned out to be somewhat problematic.”

While Close believed the intentions for the warning came from a good place, he understood how it could be seen by students.

“I think people turned out to make sure their classroom was safe for all students and welcoming for all students, and had a consequence that was unintended. Generally I think we learned a lot from that, and realized that for district approved novels, we don’t need permission letter,” Close said. “I think it was kind of a one-time-thing that was basically people working through new material.”

Close emphasized once again how this became a preemptive action by those currently acting in the book.

“I have to say I wasn’t heavily involved in that decision. I wasn’t the department head last year and I did not teach 9th grade last year, so I was not directly involved in that, but my sense is that it had a lot more to do with anticipation of student and parent pushback, and sort of wanting to be proactive from that instead of reactive, which is a good thing, to be proactive,” Close said. “But like I said, unintended consequences sometimes happen. I think also there’s a big difference between 9th grade and 12th grade, and we talk about teaching material that some perceive as teaching adult content.”

Regardless of what novels had permission slips, Close emphasized the district itself limits little to none of the school curriculum.

“This is my fifth year here, and there’s zero censorship. This district offers lots of freedom for what we teach and there’s a ton of autonomy and so the difference between censorship and school appropriate-ness is that sometimes there’s a fine line, but there’s a difference,” Close said. “Basically, censoring a book and saying “You cannot teach this” is a little bit different than saying “This isn’t an appropriate age to teach this novel.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

A petri dish and many different types of bacteria are not things that the average high school student wants to spend their time around. But for Nalini...

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)

![All smiles. The group poses for a photo with last year’s book, “This is Our House,” along with their award for third Best in Show. Meikle, who was an Editor-in-Chief for the yearbook last year as well, holds both and stands at the center of the group. “That was an amazing feeling, going and grabbing the third place award,” Meikle said. “All of it paid off. I cried so much over that book, being able to receive [the award] was one of the highlights of my high school career, it was like the coolest thing ever.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/8bookpose_philly-1200x800.jpg)