The power and glory

It is an irony not lost on me that reporting on my own nomination to a journalism convention requires I commit the cardinal sin of reporting, that is, I cannot write this article without making myself the story.

There’s no real hope of formatting this introduction in a way that doesn’t seem braggadocios or self indulgent, and so I’ll simply offer as means of exculpation that I tried to keep my self-congratulation as brief as possible.

This summer, I was our state’s representative to the Al Neuharth Free Spirit and Journalism conference. An annual celebration of the five freedoms of the first amendment, the conference, named for USA Today founder Al Neuharth, is held at the Newseum in Washington DC. One student from each state and another from the District of Columbia is selected on the basis of two personal essays, two letters of recommendation, and three examples of their journalistic work.

The conference, put on by the Freedom Forum, is a five day crash course through the past and present of America’s rich relationship with protests and the press.

On our first day, we got the opportunity to visit the Newseum itself–to see fragments of famous papers, and pictures of reporters at work and, of course, images from history. There was one that stood out to me, on a television, in a row of them all showing famous scenes from America’s past. It was John F. Kennedy speaking, at his inauguration, in 1960. “Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.”

It felt, in the moment, fitting. That here, alongside the next generation of writers and activists there were these reminders of the American past. Of youth movements and struggles, of young people who changed the world.

This memory grew darker and darker as the conference went on. Hanging over the entire event was the pall of contradiction. The conflict inherent to the simultaneous celebration of journalism and government. The separation between freedom and patriotism.

As the event went on, the contradiction became more pronounced. The blinding separation between the idealism inherent to the pursuit of knowledge and the immorality inherent to any structure of hierarchical power.

How was it possible that we would turn in one moment from meeting the reporter who broke the Joe Paterno scandal to in the next speaking with Bill Clinton’s press secretary Mike McCurry? One heroically confronted systemic misconduct, the other defended it. To paint them as anything other than opposites locked in diametric opposition seems unconscionable

And as the conference moved on the Kennedy quote nagged at my mind. Or more accurately the implications behind it. It seemed no longer to symbolize the hope and the beauty of our American past. As we spoke with reporter after reporter who had broken stories of horrific misdeeds by powerful men it seemed instead a grim reminder of a darker time, when the president of the United States was able to hide his affairs and accusations of assault by virtue of a complicit press.

The conference was a whirlwind, a jarring, dazzling, overwhelming five day trip of the sort where friendships are formed by force of situation. There was very little chance I wouldn’t emerge with some combination of jovial camaraderie and awed intimidation after spending every waking moment with students hand selected for sharing my ambitions and personalities. And so, if you take one thing away from this article let it be that Free Spirit is worth it for the friends alone. Make no mistake, the monuments are stunning, the conferences astounding and the lessons life changing, but the most meaningful thing I returned from Washington D.C. with was 50 of the best friends and colleagues anyone could ask for.

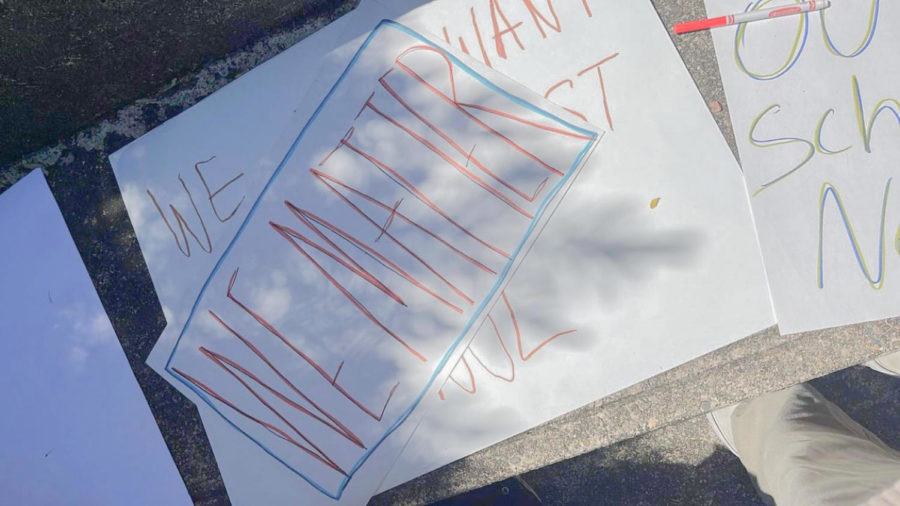

In these grim and increasingly desperate times there can be a sense of isolation. As if our alienation is individualized and our sense of helplessness in the face of atrocity is unique to us alone. There is nothing more affirming then, than meeting a collection of people from across the nation and finding that they are as well disenchanted and frustrated, and that, beyond that, they are advocating for change.

This then, should be a reminder that at a fundamental level journalism is simply the art of preserving human relations. Recording and presenting the individual actions of people and reproducing them on mass so as to promote a more understanding society.

As the conference went on a sort of tension came over me, one I have struggled to put in to words. It was not that something was wrong with our experiences, in fact, it was the opposite. It felt indecent somehow, that as journalists we were cloistered in a place of such incredible beauty and wealth, presented with the most incredible food and dressed up to look picture perfect before being paraded in front of monuments and magistrates. That we were standing in a place of power.

Every single one of us is a product of experiences and actions, a human being with a story and an irrevocable right to protection from the powerful and a voice in the direction of society. Depriving them of that is not just an affront to ethics and democracy but an act criminal inhumanity, and our obligation as journalists is not to protect or preserve the powerful, but to provide power to those who have none.

To be a journalist is to hold power in society, and that is an immense privilege. Writers and broadcasters are the gatekeepers of truth in a democracy. We can use that position to preserve our own relations and the structures that brought us to prominence.

It is not partisan, not political. The role of the press and of the people has to be more than an opposition to a single president or ideology. Our obligation is unyielding adversariality to power wherever it manifests itself. In opposition and organization against the arbitrary and inhuman divisions of humanity among lines of bigotry or greed. Our obligation is to human beings; to tell their story and change their lives. To confront the hierarchies that restrict human freedoms wherever they exist, from culture to politics to economics. And to champion, always, the cause of each and every human being.

To attend the Free Spirit and Journalism conference was the privilege of a lifetime. I urge every journalist in there junior year to consider applying. But to stand in places of power is not enough. Indeed, as a journalist, it is not anything at all.

The contrast between the celebration of protest and the insular nature of power has helped me to understand that journalism and the cause of social justice exists in constant conflict with privilege. And our responsibility as journalists and as human beings cannot be to truth or justice in isolation. The battle for a better world goes hand in hand with our right and responsibility to question the arbiters of the status quo. Any cause or movement that sees itself beyond either goal is doomed to failure.

We must understand, our cause is not just to outline problems, but to solve them. Not just to confront the powerful, but to pressure them. Because if we take one lesson from this moment it must be that our enemy is not feeling without facts, but facts without feeling. Heartless and hopeless machinations of power devoid of all humanity.

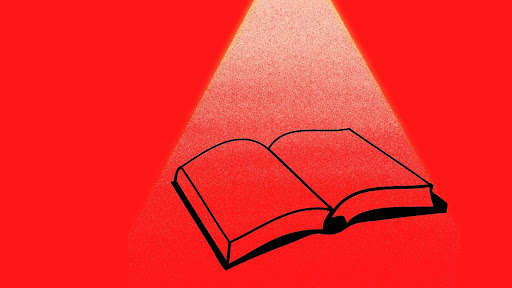

Standing alongside a generation of writers who are also protesters, of broadcasters who are also advocates, of reporters who remain unyieldingly idealistic has helped me to understand that journalism is inseparable from activism. A passive press is not a press at all. And so we must pursue with equal devotion our twin causes; to shine a light on the shadows, and to burn down the walls that cast them.

The torch has been passed and with it comes the injustices and the legacy of the past. Our cross to bear, as the leaders of the world. And so we must, as a media class, and as a generation dare to dream of a better world.

And then light the way there.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)