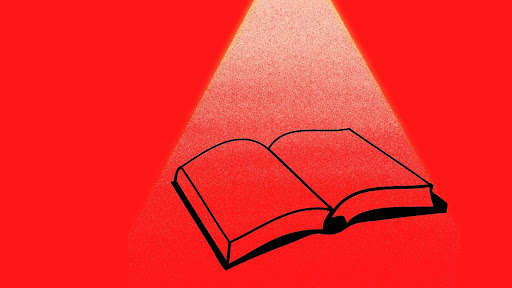

Every day needs a night: the issue of light pollution

Cars light up the freeway at 9:00 on the freeway. As commuters make their way home on 205, their bright headlights break through the shadows of the evening. Along with the harsh street lights, they fill up the area in what seems like an elaborate light show.

Turning off a light is usually seen as a way to save energy, not stop pollution. But artificial light is ironically often an issue kept in the dark to the public eye. Light pollution an extremely impactful pollutant to the environment, and its effects have become even more drastic is the past couple of years. Also known as photo pollution, it’s no longer a concern for annoyed astronomers who can’t see the stars properly; it’s now a real-world problem that must have an action against it since it’s only getting worse. According to the National Park Service, light pollution increased 6 percent from 1947 to 2000. In cities like Las Vegas, light pollution increased 8 percent annually. These statistics are only getting bigger.

Things like keeping our stadium lights on for long periods of time at night alters the natural state of the ecosystem, affecting its flora and fauna. Since there is now light that doesn’t go away at night. The overuse of artificial lights causes an effect called “sky glow” which is a perpetual glare in areas with concentrated light use. Big cities like Portland experience this phenomena.

Not only does this type of pollution alter the natural state of an area, but it affects all inhabitants living there. It alters all animals, including humans’ circadian rhythm. This causes insects and other animals to behave differently. For example, many insects, including moths are attracted to light, as well as other creatures like frogs and some birds. This increases their activity at times they usually aren’t active, changing their behavior and evolutionary niches over time. These small-scale creatures’ disruption overtime will cause large-scale environmental damage, a break in the chain that goes all the way down.

The question when it comes to West Linn is do whether or not we have policies in place. How long do we and are supposed to keep our lights on? Especially the brightest ones like our football stadium lights, which you can see from the other side of the valley.

“There isn’t so much a policy,” Rich Craghead, Head Building Engineer, said, “But we just try to turn them off as often as possible if they aren’t being used… They also run on timers, the only time the stadiums light are on, are for specific scheduled times they are being used.”

The stadium lights are 1500 mercury vapor lights, which is one of the more conservation-friendly bulbs. However despite these precautions, light is still a problem, that needs more effort put into it then turning off a light whenever you can.

Some cities are actually doing there very best to stop light pollution. In fact, towns like Flagstaff and Sedona in Arizona have become trail-blazers in combating it. Dating back to the ’70s, Flagstaff has attempted to keep its light down, for the large community of astronomers in the area. They initiated new rules like only having downward facing lights on their streets, and replacing more traditional lights, with low-watt and low-light ones. They only allowed a certain amount of light per area or lumens per area.

This not only helped with the astronomer’s cause but also benefited the ecosystem greatly, which has recently been the more concerning issue in light pollution. Now in the present, those towns still do a good job at considering their light production. Organizations like the International Dark Sky Association also educate people on the concerns of photo pollution and educate them on solutions as well, as easy as using better lightbulbs and turning off unnecessary lights. In a broader aspect, cities and government can work to reduce light pollution by imposing better policies in its facilities and educating the public on this lesser-known topic. Overall we can help create change to better our environment, cities and even our own overall health.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Iris Brucker, sophomore, had always been an answer seeker at heart. Since a young age she was constantly asking questions about anything and everything,...

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)

![All smiles. The group poses for a photo with last year’s book, “This is Our House,” along with their award for third Best in Show. Meikle, who was an Editor-in-Chief for the yearbook last year as well, holds both and stands at the center of the group. “That was an amazing feeling, going and grabbing the third place award,” Meikle said. “All of it paid off. I cried so much over that book, being able to receive [the award] was one of the highlights of my high school career, it was like the coolest thing ever.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/8bookpose_philly-1200x800.jpg)