Reading into censorship

Districts across Oregon faced with parental pressure to restrict library materials

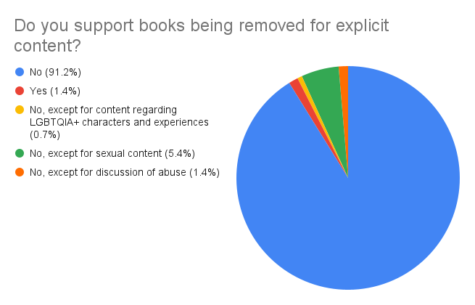

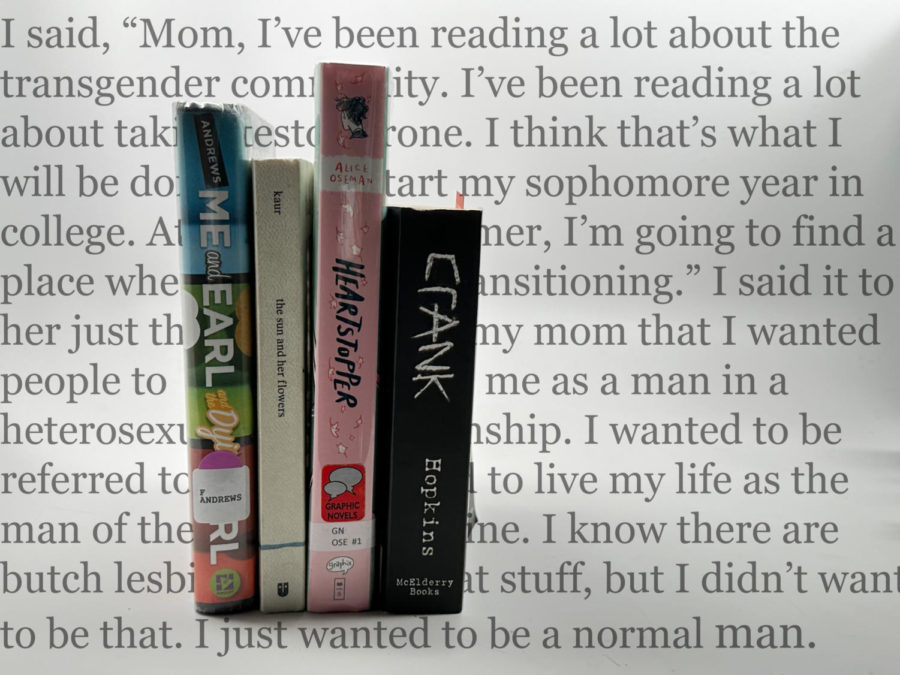

Among eight others, Heartstopper has been put up for review in district libraries. The basis for this call for removal has been questioned by some students, including class of 2018 alum Olivia Olmsted.

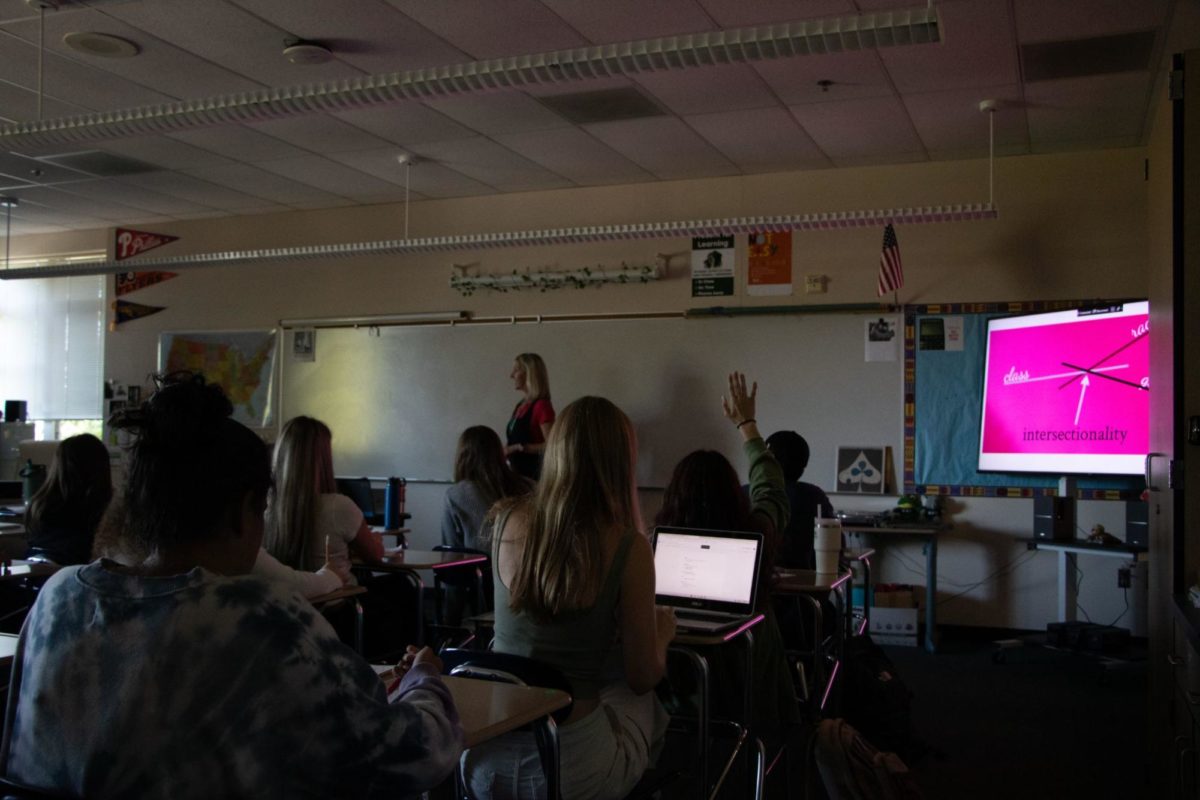

Public school curriculums facing censorship is nothing new. Conservative legislation restricting what can be taught in relation to LGBTQ+, race, and sex education have become more common across the United States. Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, formally titled Parental Rights in Education, is just one of many bills pushing for censorship that have emerged in the past few years— 2022 saw a 250% increase in proposed educational censorship orders from the previous year.

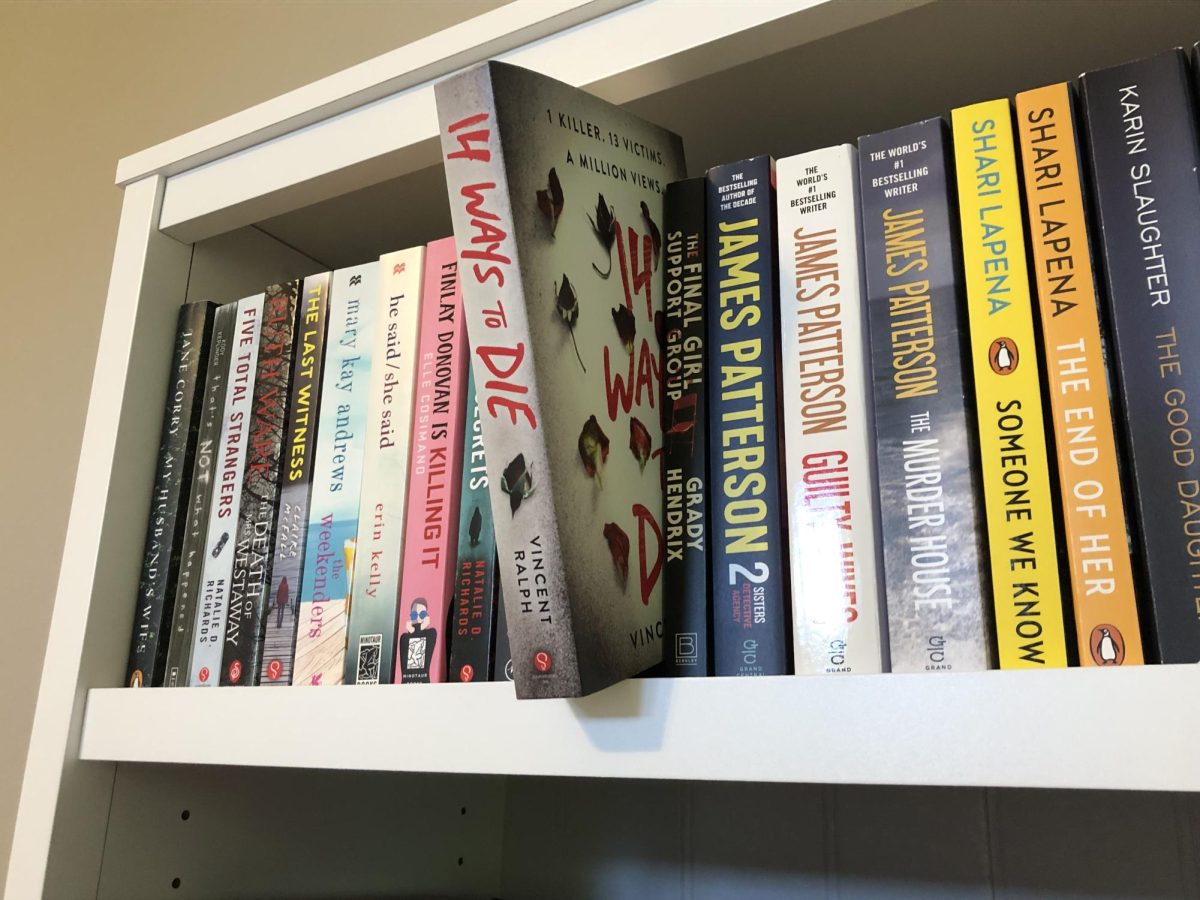

Across 32 states, over 1600 books were banned from school libraries in the 2021-2022 school year. This number is abnormally high in comparison to previous years. Much of this can be attributed to actions taken by conservative local, state, and national groups pushing for the removal of books with content they deem inappropriate.

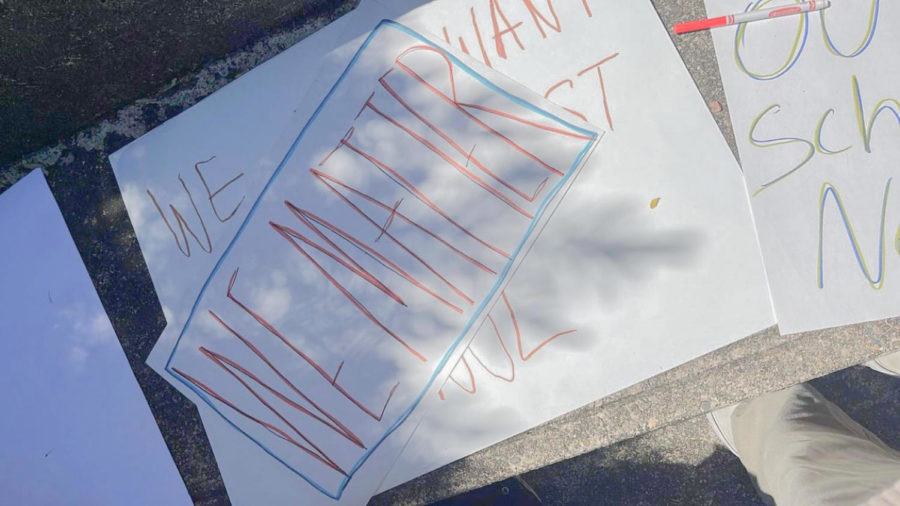

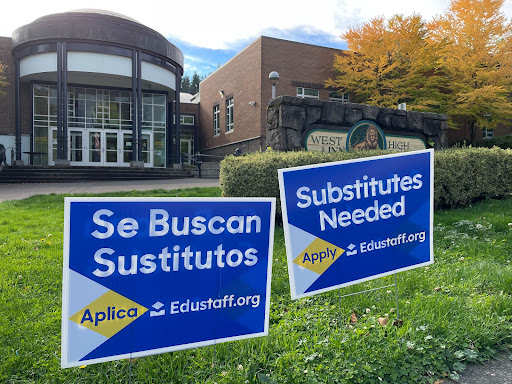

As this educational censorship movement continues to become more widespread, its advocates have been speaking up across the nation. West Linn-Wilsonville School District (WLWV) school board meetings are held monthly. During the Nov. 14 meeting, a group of concerned parents associated with the Oregon Moms Union (OMU) voiced their discomfort with the mature content accessible in school libraries. Since then, the group has also made an appearance at the Dec. 5 and Jan. 9 meetings to request the removal of certain books in school libraries.

The Oregon Moms Union

Founded in 2021, The OMU’s mission is to “help organize parents to fight for their kids’ right to a quality education” according to their website. With over 90 ‘school district captains’, they’ve expanded across Oregon, encouraging parents to send emails to their children’s schools to request changes to curriculum, library resources, and sex education. Tricia Britton is one of the WLWV district captains who spoke at the recent board meetings.

“It’s not a myth that children’s innocence should be protected,” Britton said. “Stop exposing children to unnecessary, uneducational sexual books, and protect them from harm and potential triggers.”

The school board has since announced a new review process for books of concern. The review process will include district admin and librarians as well as community members and parents. Decisions will be made based on a full review of the book’s material and reviews from professional organizations such as the American Library Association, rather than out of context passages.

“The book ‘Gender Queer’ [by Maia Kobabe], has been removed from several Oregon libraries,” Britton said. “You use the American Library Association, and they gave this book a positive review similar to all [eight] books in question. This goes to prove that these resources you are using are not reliable, but the one resource that has stood the test of time to be most reliable is a parent.”

The review process will take into account the ages that the books are accessible to (high school, middle school, or elementary). After the completion of the review, books will either be left in place, relocated to an advisory location, or removed from the library entirely. The Office of Teaching and Learning, including David Pryor, who oversees district libraries, will conduct complete reviews for any complaints received. We want to continue to make sure that our students are really proud of their libraries, and that they feel like they have books that they want to read. — David Pryor

“We’re going to take our time and look at each book individually,” Pryor said. “I know how important school libraries are for students to have access to a range of ideas, and we want to continue to make sure that our students are really proud of their libraries and that they feel like they have books that they want to read.”

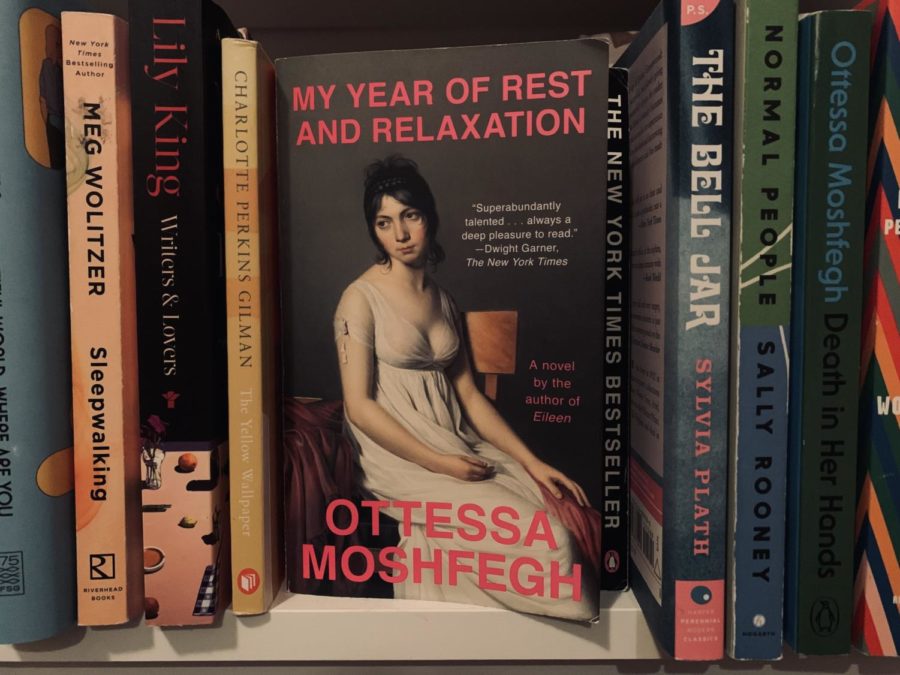

Books of concern

The eight books being reviewed contain mature content regarding sexuality, gender identity, and drugs. One of the more explicit books that was complained about is “Crank” by Ellen Hopkins.

“Crank” follows Kristina, a high school student, as she falls into meth addiction and finds herself in increasingly dangerous situations after visiting her drug-addicted father for three weeks. After she returns to her home life, she connects with drug dealers, falling deeper into addiction. She quickly loses interest in daily activities— she barely eats, sleeps, her relationships with friends and family crumble, and her grades suffer.

At the same time, Kristina’s behavior becomes increasingly reckless as she begins lying to her parents, sneaking out to meet up with boys, and ends up pregnant with her rapist’s child.

There’s no debate that graphic descriptions of sexual abuse and drug usage is uncomfortable, and that it should not be glorified. However, the author simply depicts the struggle that the main character faces. When scenes of sexual assault are described, it does not say that assault is acceptable and should be normalized, but rather shows the impacts that follow. The content is supposed to make you feel uncomfortable— the content isn’t designed to make the reader want to rape somebody.

It’s also notable that four out of the eight books that were complained about contain content representing the LGBTQ+ community. “Heartstopper Vol. 2” by Alice Oseman is one of these titles. The OMU complains that the book features sexually explicit content— but the characters are never shown doing anything more than kiss, and are never shown nude.

At the Dec. 5 school board meeting, Olivia Olmsted, class of 2018 alum, shared her personal experience with representation as a LGBTQ+ student.

“I would like to share two things about myself. I’m non-binary, and I’m gay,” Olmsted said. “They’re an important part of my identity, and they’re not a choice nor a political statement. Books did not coerce, indoctrinate, or trick me into believing these facts about myself.”

“Heartstopper” alongside “Beyond Magenta” by Susan Kuklin, “Lawn Boy” By Jonathon Evison, and “Flamer” by Mike Curato are all centered around LGBTQ+ experiences. The most explicit content shown in these novels is discussion around sexuality, gender, and bullying. “Beyond Magenta” is a collection of stories from various members of the LGBTQ+ community, describing the support they received growing up and how that shaped their lives. “Lawn Boy” follows a biracial, gay young adult as he navigates his life. “Flamer” revolves around a teenager struggling with self-hate, sexual orientation, and religion.

“Having ‘Heartstopper’ where queer characters are shown in a healthy relationship, coming out to friends and family, and just happy, could have helped me begin my journey of coming out and self-acceptance so much earlier,” Olmsted said. “I didn’t know any out queer people, and I rarely, if ever, saw myself portrayed positively in books and media.”

School board responds

As the controversy has persisted for months now, Kirsten Wyatt, member of the WLWV School Board of Directors, and Kathy Ludwig, District Superintendent, spoke up about the issue.

“I want to make it very clear that I do not and I will not support banning books from our school libraries,” Wyatt said. “I support a parent’s choice to be involved in their child’s education. One parent’s judgment or preference on a book for their family should not be extended to other students or their families.”

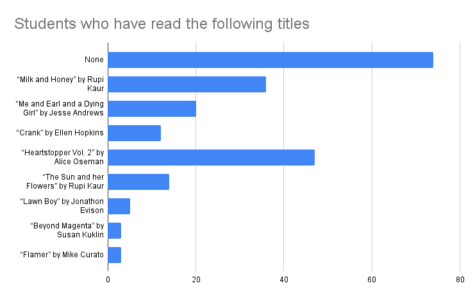

Wyatt is not alone in her view. In a poll of high school students, 91.2% of students stated that they were against books being banned. Despite the recent rise in academic censorship movements, public opinion has not changed.

Parents are always capable of restricting books from their own children, and nobody is required to read content that makes them uncomfortable.

“If a parent wants to make that choice for their child, saying you can’t read that book, it’s a really simple process to make that happen,” Wyatt said. “Our librarians make a note of it. They know our kids, and they respect parent choice.”

This aside, the review process is currently taking place. “We are using our review process to take a look at these eight specific [books] through a review group,” Ludwig said. “There will be a full review of the complaints and reading of the comments that came in— both ones in support of the texts and ones with concerns.”

As the review is being completed, it’s safe to expect more discourse around these censorship issues. “Despite the Board Chair shutting the meeting down twice, [we] expect these explicit books and their review process to be on the agenda in February,” the OMU posted on social media.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Kaelyn Jones, junior, has been involved with wlhsNOW since her freshman year. As the first multimedia editor, she hopes to push podcasting and broadcast...

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)

Spencer

Mar 12, 2023 at 10:49 am

Great article! As a parent of a middle school child in West Linn, I wondered how bad the content would be. Thank you for sharing the content in context rather than what the moms group has done. I am very curious how these books were initially “discovered” – my assumption is the group targeted subjects around LGBTQ and BIPOC, and uncovered these. I doubt they have reviewed the thousands of books in school libraries in an unbiased review. If I was a non-Christian and didn’t want my kids reading the “objectionable” content of Christian themes should I then make a stink about banning those books?

Their arguments are ridiculous and frivolous, and damaging to our kids.