Sourcing sustainable housing

Why West Linn needs to follow Eugene’s lead in banning natural gas hook-ups

The residential sector accounts for roughly 15% of natural gas consumption. As Gov. Tina Kotek has called for 36,000 new houses to be built each year, it’s vital for Oregon to move towards more sustainable energy sources in the face of climate change.

As dozens of species go extinct each year, destructive weather strikes cities, and dire droughts impact thousands, climate change seems to constantly populate news cycles and social media feeds. But, as overwhelming as all of it can often feel, there are people who are fighting for a positive change.

In 2020, former Gov. Kate Brown addressed the climate crisis in an executive order with the goal of reducing carbon emissions by at least 80% by 2050. To meet the goal, action needs to be taken across the state— and Eugene has made sustainability one of their goals.

How to approach sustainable housing in the face of extreme population growth is a question with no single answer. On Feb. 6, Eugene City Council passed Council Ordinance No. 20681 with a vote of five to three and the support of mayor Lucy Vinis. With this, Eugene became the first city in Oregon to officially begin phasing out natural gas, banning it in all new developments of three stories or less.

The ordinance, which was approved by the Eugene City Council, was created with the goal of decreasing carbon emissions. By enacting this ordinance, Eugene is setting a precedent for the rest of the state to follow.

Jillian Gregg is an instructor at Oregon State University, teaching Introduction to Climate Change to over 1200 students every year. She has devoted her professional life to studying and spreading awareness about climate change.

Already, we have 50% more CO2 in the atmosphere than we did before the Industrial Revolution. — Jillian Gregg

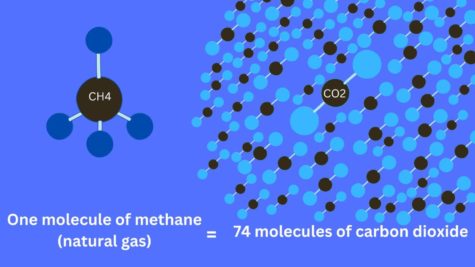

“Natural gas is methane. And methane is a 74 [times] stronger greenhouse gas compared to CO2. So for every molecule of methane you put into the atmosphere, it’s like you put 74 molecules of CO2 into the atmosphere,” Gregg said. “Already, we have 50% more CO2 in the atmosphere than we did before the Industrial Revolution. And it’s all due to humans burning fossil fuels.”

Reducing, and eventually eliminating, natural gas usage is a vital step in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, roughly half of the homes in America used natural gas for space and water heating, as well as stoves and ovens. The residential sector accounts for roughly 15% of national natural gas consumption.

“There’s plenty of arguments that [natural gas] is not the better alternative compared to coal,” Gregg said. “When we collect it, a lot of that gas escapes into the air before we ever even utilize it. All throughout the U.S., there’s pipelines, and they leak.”

Eugene isn’t the only area in Oregon that has expressed interest in policies like these before. Over the past few years, Milwaukie and Multnomah County have both passed resolutions to ban natural gas hookups in new construction and begin to phase it out in city-owned buildings during 2024.

Whether these resolutions will lead to significant action is not yet clear. That’s why Eugene making this ordinance official is such a major step forward— instead of just setting goals, it lays out a plan for real, unassailable action.

The West Linn Sustainability Advisory Board (WLSAB) focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Co-chairs Mike Carlson and Greg Smith work to move West Linn towards a sustainable and carbon neutral future.

“The Sustainable West Linn Strategic Plan really looks at a variety of different kinds of issues related to water conservation, natural resource protection, dealing with energy, and the reduction of fossil fuels,” Smith said. “It also explores issues tied into community health and well being.”

The Sustainable West Linn Strategic Plan outlines a series of goals to move towards a more pleasant and environmentally friendly city. Most notably, it aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in existing West Linn city facilities and operations by 80% by 2040.

Reducing emissions by that much is undoubtedly an ambitious goal— but a necessary one if we’re looking to create a sustainable future. However, there hasn’t been any significant action taken by West Linn city officials to move towards meeting these goals.

“One thing that we’ve been working with the city to do is to encourage them to electrify their fleet and to promote electric vehicles within the city,” Carlson said. “They may have a couple electric vehicles, but the majority of the city fleet is still just conventional internal combustion engines.”

West Linn needs action. Eugene has done something that no other city in Oregon has done yet, and their actions are trailblazing a path that West Linn, Portland, and all of Oregon needs to follow.

WLSAB meetings are open to the public from 6-7:30 p.m. every third Thursday of the month. Community members showing up and encouraging change is an important way to help push progress forward.

Would implementing a similar ordinance in West Linn be enough to completely eradicate the impacts of climate change? No. But it’s a step in the right direction. Effective legislation is the only way to move towards a sustainable future. On a large scale, people and corporations have proven that they will not take the necessary action on their own— we need laws.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

Kaelyn Jones, junior, has been involved with wlhsNOW since her freshman year. As the first multimedia editor, she hopes to push podcasting and broadcast...

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)