Parents and athletes perpetuate ref shortage

Limited number of referees is an alarming sign of parent and athlete entitlement

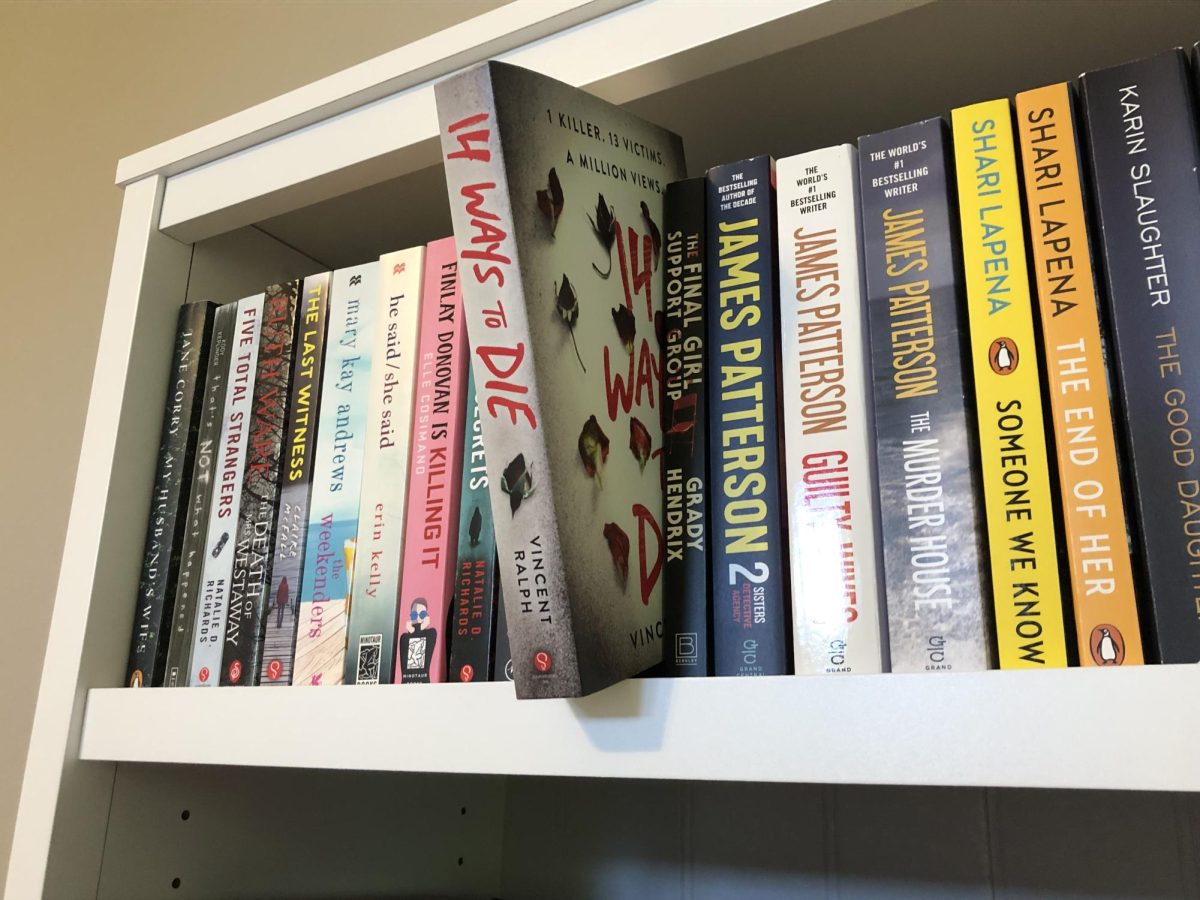

On Dec. 9, 2022, an official closely watches as Audrey Sepp, junior, gets trapped in the corner. Though the referee shortage is a local problem, it’s also a national issue–over 50,000 referees have left since the 2018-2019 school year.

You can hear the swish whisper throughout the gymnasium and the crowd, on their feet, go crazy. Though not all— some are sitting down, sullen, stunned. The buzzer blares. The losing team is sent home, but the starting center’s parents storm onto the court, heading straight for the officials to give them an earful. A call on the court did not sit well with these parents— but why did they need to go out of their way to tell the official the call was wrong?

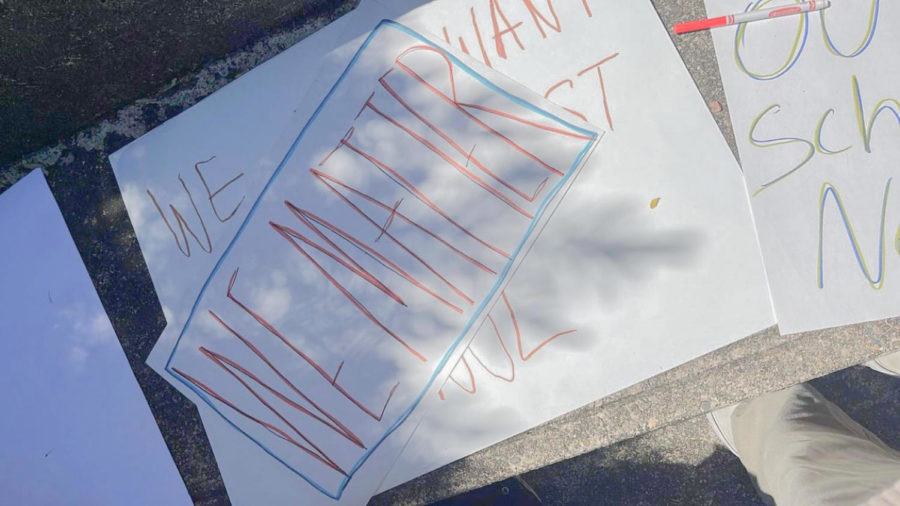

According to the Oregon Student Activities Association (OSAA) handbook, “All cheers, comments and actions shall be in direct support of one’s team. No cheers, comments or actions shall be directed at one’s opponent or at contest officials.”

Less people have applied to become referees due to the verbal abuse. Additionally, there has been an evident decrease in referees over the years, but a significant decline since the pandemic. This development has repercussions. On Feb. 16, Trevor Menne, principal, sent a statement about sportsmanship, highlighting expectations to respect game officials.

“Please know, that in accordance with OSAA guidance, spectators who fail to meet these expectations could potentially be banned from current and future interscholastic events,” the email read.

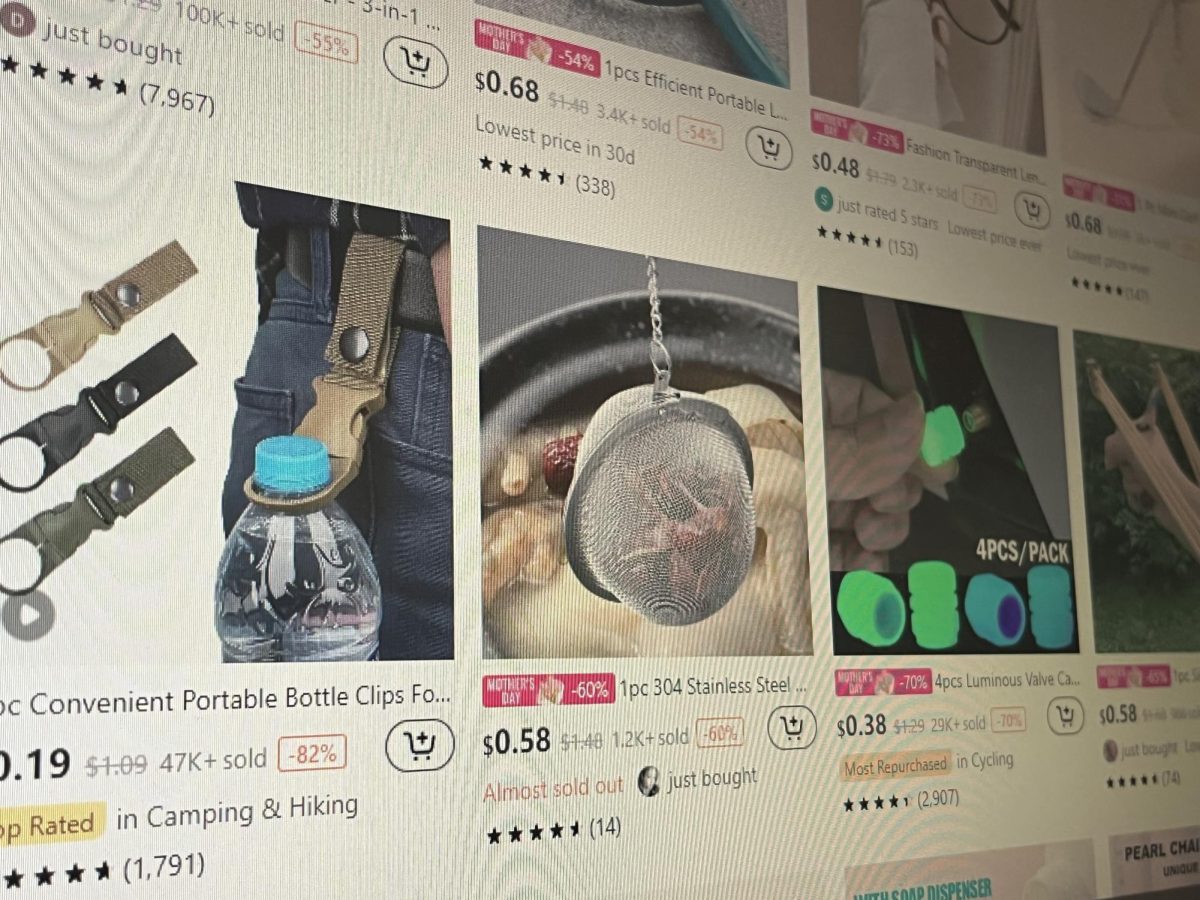

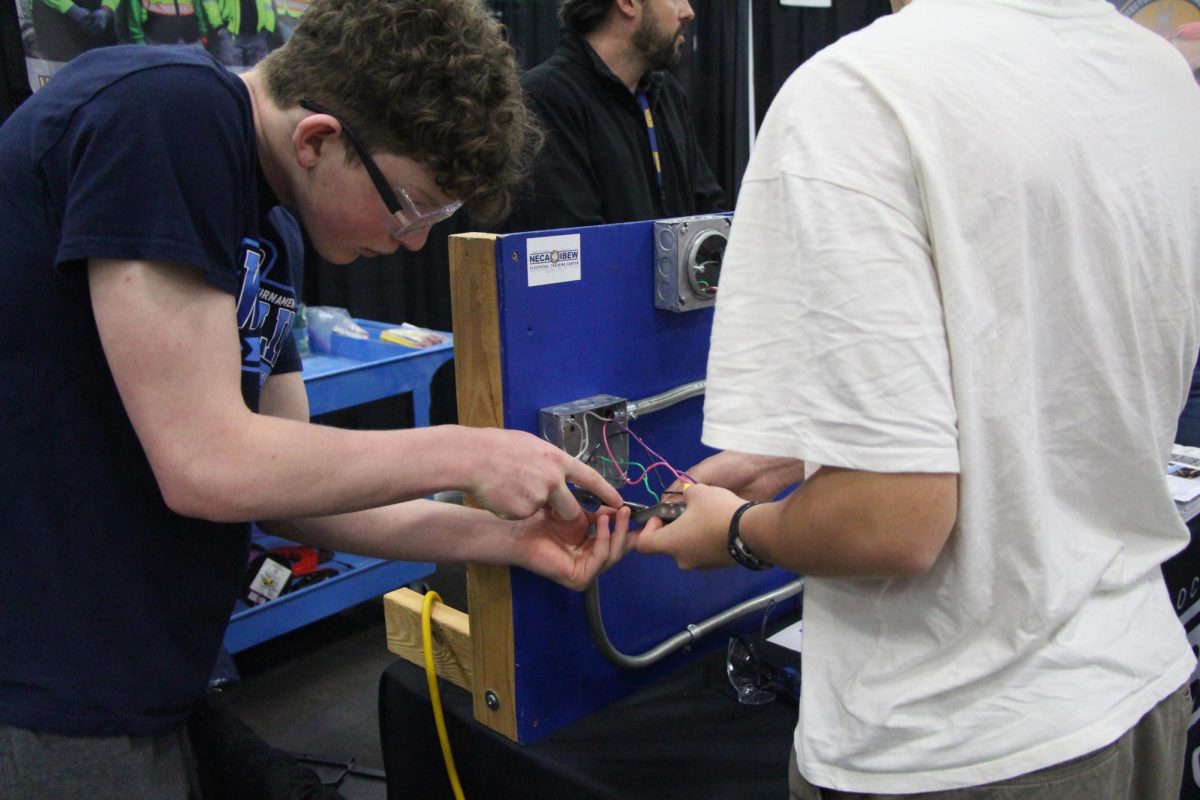

Additionally, the ref shortage has had an impact on event planning. Brigham Baker, athletic director, has needed to communicate with referee associations and OSAA regarding referee planning.

“We basically don’t have enough referees to service all of the games in our high school Association, more specifically the Portland metropolitan area,” Baker said. “This year we’ve had to move games off of the traditional days. Traditionally varsity football [is] on Friday, we move those to Thursday. Basketball we’ve played on Wednesday and Thursday, and on Monday. [In] baseball, they play a lot of games throughout the course of the week, but we could have one umpire [for the] game rather than the traditional two.”

They’ll scream at you. They’ll call you certain things, not in my personal experience, per se, but I’ve talked to other refs who’ve had kids hit them, kick them, strike them which isn’t all that great either.

— Karah Highland

To dissect this problem in our sports system, let’s go down another layer. Club sports are an option for student athletes, though expensive, sometimes up to “$10,000 per year,” Baker said. However, a lot of the community has the money as 29.2% of West Linn’s population has an income of $150,000— 10% of Oregon reaches this data point. With the influx of finances, club sports are more accessible.

This creates a dilemma within high school sports. Parents pay their child to be a part of this club team, but the clubs are more inclined in giving praise to the child, because they want the money. Therefore, parents get the idea that their child is better than they actually are.

High school coaches will tell parents their child, who gets praise under a particular club, isn’t that good, because their job is to improve the team and they are not motivated by money. Parents become outraged as they have the idea their child was a starter, not a bench player, according to their club’s assessment.

This outrage can be seen on the court. It’s not uncommon that parents inflict verbal abuse to referees. They feel justified in their actions, because they invested finances into their child’s athletic development.

In most cases, the referees are in the wrong place at the wrong time, and they have absolutely no information about the athlete’s family’s wallet. Karah Highland, senior, referees kindergarten through eighth grade age groups.

“A lot of the time, parents will come up across the court during the game,” Highland said. “[They would] tell me that it was a three point instead of a two point or they’ll mistake which team is scoring and they’ll tell you that you need to fix it when there’s really no problem.”

Though, parents aren’t the only ones causing conflict with referees. When clubs give the indication that the athlete is progressing well, they will believe that but when they meet strife in the high school system, they will still have the idea that they are better. Like the parents, athletes can become angry and make some excuses for their “underperforming” play, which leads to more pointing at referees.

“A lot of the players will get upset with certain calls or lack thereof calls,” Highland said. “They’ll scream at you. They’ll call you certain things, not in my personal experience, per se, but I’ve talked to other refs who’ve had kids hit them, kick them, strike them which isn’t all that great either.”

Now, let’s consider some options to improve referees’ conditions. Officially Human, a website that aims to give officials more respect, has provided data on the nationwide shortage of referees. In a survey conducted by this website, which consists of 15 states, 60% of officials left because of verbal abuse from the fans, and 50% because of coach abuse. The officials were given two options to choose from. Officially Human is providing data to spread awareness about the seriousness of this issue.

On a more local level, work can be done to lessen the impact of club sports. Families could try solely personal trainers since most have the money as 49.9% of West Linn’s population has an income of $100,000.

“Personal trainers in my opinion, are really good [since they] motivate the people to do those workouts that they have in front of them,” Baker said. “I’d say probably 75% of their job is actually motivating that person to get up and do it, so [I like] personal trainers. I don’t think they’re required for everybody, but if kids want to take things to that next level, they’re certainly not a bad idea.”

Overall, the situation is this: club sports are creating an illusion that an athlete is better than they are, and while these athletes seemingly underperform on the high school stage, underlying outrage goes towards referees. Above all else, if you make that choice to verbally abuse the referee, eventually, your child–or yourself–may not get to play the sport.

Your donation will support the student journalists of West Linn High School. Your contribution will allow us to continue to produce quality content by purchasing equipment, software, and continuing to host our website on School Newspapers Online (SNO).

In addition to being the Web Editor-in-Chief, Joseph Murphy, senior, also enjoys running with the cross country team. Journalism has proved to be Murphy’s...

![Game, set, and match. Corbin Atchley, sophomore, high fives Sanam Sidhu, freshman, after a rally with other club members. “I just joined [the club],” Sidhu said. “[I heard about it] on Instagram, they always post about it, I’ve been wanting to come. My parents used to play [net sports] too and they taught us, and then I learned from my brother.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/MG_7715-2-1200x800.jpg)

![The teams prepare to start another play with just a few minutes left in the first half. The Lions were in the lead at halftime with a score of 27-0. At half time, the team went back to the locker rooms. “[We ate] orange slices,” Malos said. “[Then] our team came out and got the win.”](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IMG_2385-1200x800.jpg)

![At the bottom of the third inning, the Lions are still scoreless. Rowe stands at home plate, preparing to bat, while Vandenbrink stands off to the side as the next batter up. Despite having the bases loaded, the team was unable to score any runs. “It’s just the beginning of the season. We’re just going to be playing out best by June, [and] that’s where champions are,” Rowe said.](https://wlhsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_3077-1200x900.jpg)